the complete history of

Radio Swan - Radio Americas - Swan Island

Radio Swan – Cuba, Castro, CIA

The secret radio station that wasn't!

During the annual "Free Radio Meeting" in Hochdahl, Chet Reuter gave a presentation on Radio Swan. He had listened to this station himself in the 1960s and followed the reports about the mysterious station in the American press. My interest in shortwave listening and radio in general only began in 1970, so I was not familiar with Radio Swan. However, I did remember secret and underground stations such as Radio Rebelde (B01, page 5 and B02, page 8), La Voz del C.I.D., Radio Clarin and others - stations I was interested in even then because of their unofficial character. When I learned that declassified documents from the CIA archives (about 12 million pages so far) contained information on Radio Swan, my curiosity was finally aroused. For some years now, most of these formerly secret documents have also been available on the internet. This has brought to light many facts about Radio Swan about which one could only speculate until now.

During the annual "Free Radio Meeting" in Hochdahl, Chet Reuter gave a presentation on Radio Swan. He had listened to this station himself in the 1960s and followed the reports about the mysterious station in the American press. My interest in shortwave listening and radio in general only began in 1970, so I was not familiar with Radio Swan. However, I did remember secret and underground stations such as Radio Rebelde (B01, page 5 and B02, page 8), La Voz del C.I.D., Radio Clarin and others - stations I was interested in even then because of their unofficial character. When I learned that declassified documents from the CIA archives (about 12 million pages so far) contained information on Radio Swan, my curiosity was finally aroused. For some years now, most of these formerly secret documents have also been available on the internet. This has brought to light many facts about Radio Swan about which one could only speculate until now.

Besides Radio Swan, there were further interesting radio activities from this remote island. In the last section (The Island) I report about it. The total reading time for this post is about 70 minutes.

Notes on the links: the combination of letter and numbers leads to the corresponding source in the bibliography, where possible the page numbers open the original document directly on the corresponding page.

Swan Island (German: Schwaneninsel, Spanish: Islas del Cisne), coordinates: 17° 24' 20'' N, 83° 56' 23'' W, Google Plus Code: 769RC346+94 in April 2008. Bottom left is the coral reef Bobby Cay, above it the main island Great Swan and to the right Little Swan. Little Swan is a protected area and is very difficult to access because of the rugged coral coast. (Google Earth)

Abstract

Radio Swan, renamed Radio Americas in November 1961, broadcast from Swan Island in the Caribbean on medium and short wave from May 17, 1960 to May 15, 1968 to orchestrate the overthrow of Fidel Castro. The station was operated by the CIA at enormous expense, disguised as a commercial station. During the Bay of Pigs landing (April 17, 1961), the station provided tactical support to the landing forces. Despite several (feigned) changes of ownership, there were suspicions from the beginning that there was a connection between Radio Swan and the CIA. But it was only after the first secret documents on the American efforts to overthrow Fidel Castro became publicly available at the end of the 20th century that this was finally confirmed. The evaluation of these and other documents relating to Radio Swan/Americas and related CIA propaganda activities are the basis for this article. Much of the information is being published here for the first time in German (some of the information in this translation have not even appeared in English publications). Finally, after more than 60 years, this is the (almost) complete story of the CIA's Radio Swan operation.

Radio Swan, renamed Radio Americas in November 1961, broadcast from Swan Island in the Caribbean on medium and short wave from May 17, 1960 to May 15, 1968 to orchestrate the overthrow of Fidel Castro. The station was operated by the CIA at enormous expense, disguised as a commercial station. During the Bay of Pigs landing (April 17, 1961), the station provided tactical support to the landing forces. Despite several (feigned) changes of ownership, there were suspicions from the beginning that there was a connection between Radio Swan and the CIA. But it was only after the first secret documents on the American efforts to overthrow Fidel Castro became publicly available at the end of the 20th century that this was finally confirmed. The evaluation of these and other documents relating to Radio Swan/Americas and related CIA propaganda activities are the basis for this article. Much of the information is being published here for the first time in German (some of the information in this translation have not even appeared in English publications). Finally, after more than 60 years, this is the (almost) complete story of the CIA's Radio Swan operation.

The politics

With the new government formed under Fidel Castro in early 1959, the US lost its influence on Cuba. Previous US efforts to form a reform government that favoured US economic interests, thereby guaranteeing stability and security for the development of US investment and capital growth plans in Cuba, were thus rendered moot. In order not to further weaken the ailing political relations, Washington refrained from using the Voice of America for direct propaganda broadcasts (C04, page 3).

With the new government formed under Fidel Castro in early 1959, the US lost its influence on Cuba. Previous US efforts to form a reform government that favoured US economic interests, thereby guaranteeing stability and security for the development of US investment and capital growth plans in Cuba, were thus rendered moot. In order not to further weaken the ailing political relations, Washington refrained from using the Voice of America for direct propaganda broadcasts (C04, page 3).

In August 1959, the CIA began drafting a general strategy paper on paramilitary actions in Latin America (A06, page 4). On October 27, 1959, Joseph Caldwell King, head of the CIA's Western Hemisphere Division, proposed a propaganda operation specifically aimed at Cuba (A08, page 204). This gave rise to establishing Division 4 (WH/4) in January 1960 (A06, page 5). From March 1960, David Atlee Phillips directed the propaganda activities of this department (he had already proven himself in the propaganda programme PBSUCCESS in Guatemala in 1954) and developed a programme aimed at liberating Cuba from the revolutionary leader Fidel Castro (A09, page 10 – A23 and C29). The centrepiece of David Phillip's propaganda activities was a transmitter on Swan Island (A08, page 212). This plan was approved by President Eisenhower on March 17, 1960 (A10 and A23). By the summer of 1960, however, it was becoming clear that the only way to orchestrate a political and military collapse of Cuba was through an external armed attack (A08, page 292). A monumental propaganda offensive was launched to mobilise the opposition and prepare for the Bay of Pigs landing on April 17, 1961 (C29). From an initial staff of 40 in January 1960, the WH/4 department grew to 588 people by April 1961 (A06, page 8). Originally, costs of $4.4 million were planned for the entire operation in 1960 and 1961, with $1.1 million budgeted for setting up and running Radio Swan alone (A09, page 12). In fact, total costs of over $46 million were incurred in 1960 and 1961 (A06, page 66).

The advent of transistor radios in the 1950s (cheap and usable everywhere) made radio one of the most important propaganda tools at the time (along with leaflets, newspaper takeovers and other subversive efforts). Already in 1954, the CIA operation PBSUCCESS against Guatemala was proof of the successful use of radio propaganda. In President Kennedy's words, speaking to a group of CIA specialists: "As military measures are turning more deadly, and a growing number of nations have access to these, subversive war, the war of guerrillas and other confrontational forms will acquire greater importance. As thermonuclear weapons become more powerful and the opportunities to use them become further reduced, subversive war takes on an increasingly important role." (B06)

After the failed landing at the Bay of Pigs, the CIA continued its actions against Fidel Castro. A report from October 1961 (A12, page 3) states that in addition to Radio Swan, sixty other Latin American stations as well as three stations in Florida were broadcasting anti-Castro programmes. Even a broadcasting ship was ready. In November 1961, this secret programme to sabotage and infiltrate Cuba and eliminate Fidel Castro was approved by President John F. Kennedy as "Operation Mongoose" (B03, page 2 and B05, page 101). However, in the documents declassified so far, no direct references to Radio Americas funding can be found after 1962. Operation Mongoose, launched in 1961, had an annual budget of $5.3 million, of which $90,000 per month went to Cuban exile groups (A28).

With Castro's turn towards Russia and the resulting Cuban Missile Crisis (October to December 1962), Radio Americas' propaganda activities once again took on special significance. In April 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson abandoned the goal of eliminating Fidel Castro. As a result, financial support and thus Operation Mongoose was discontinued in June 1965. However, the CIA had other avenues to access funds that could not be traced in detail. For example, the New York Times reported on April 27, 1966 in a five-part series (C35) on the work of the CIA that in 1964 the Kaplan Fund, on behalf of the CIA, had paid out at least $400,000 to research institutes in Latin America.

It is also striking that the various corporate constructs set up by the CIA were headed by people who also held positions as bank directors, real estate brokers or lawyers (C08, page 28 und page 29). The suspicion is that money from the CIA was channelled into the radio station through their bank connections.

Radio Swan and its programmes

The Revolution Betrayed

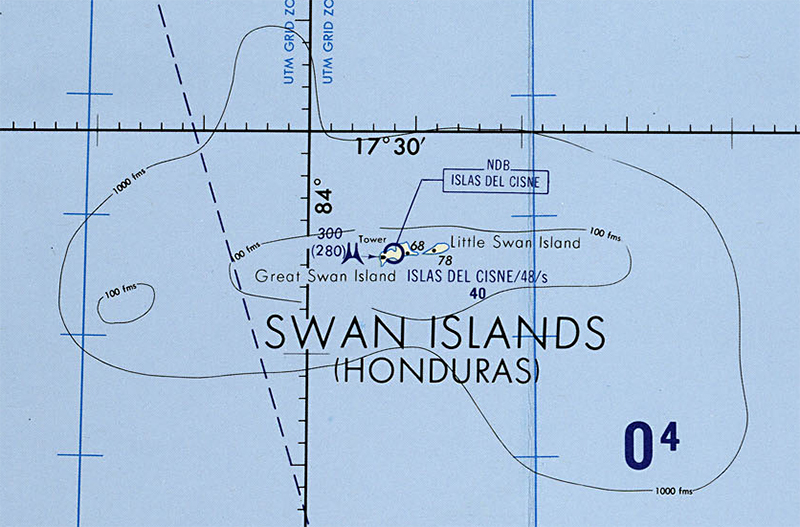

The central point of the propaganda offensive against Castro launched in 1960 was Radio Swan (later renamed Radio Americas). The CIA was given the task of setting up a powerful medium- and short-wave transmitter outside of the territorial borders of the USA within 60 days. The small Caribbean Swan Islands (two islands - Great Swan and Little Swan and a coral reef - Bobby Cay, in total approx. 3.1 sq. km in size, 17° 24' 20'' N, 83° 56' 23'' W, Google Plus Code: 769RC346+94) were chosen as the location. With the help of the U.S. Navy, an airstrip was built and the broadcasting equipment was brought to the main island (Great Swan). Originally, Radio Swan was supposed to operate as an underground station disguised as a secret missile and space project (A11, page 131). However, at the Navy's request, the CIA decided to disguise it as a commercial station. The Navy feared that it would have trouble explaining itself if its involvement in an underground CIA radio station became known (A11, page 131 and A08, page 215).

The central point of the propaganda offensive against Castro launched in 1960 was Radio Swan (later renamed Radio Americas). The CIA was given the task of setting up a powerful medium- and short-wave transmitter outside of the territorial borders of the USA within 60 days. The small Caribbean Swan Islands (two islands - Great Swan and Little Swan and a coral reef - Bobby Cay, in total approx. 3.1 sq. km in size, 17° 24' 20'' N, 83° 56' 23'' W, Google Plus Code: 769RC346+94) were chosen as the location. With the help of the U.S. Navy, an airstrip was built and the broadcasting equipment was brought to the main island (Great Swan). Originally, Radio Swan was supposed to operate as an underground station disguised as a secret missile and space project (A11, page 131). However, at the Navy's request, the CIA decided to disguise it as a commercial station. The Navy feared that it would have trouble explaining itself if its involvement in an underground CIA radio station became known (A11, page 131 and A08, page 215).

As early as May 14, 1960, the New York Times published a report on the new radio station (C33). Three days later, on May 17, 1960, the first test transmissions were broadcast on medium wave (A08, page 214). Radio Swan, "La Voz Internacional del Caribe", officially started broadcasting on June 1, 1960 (D04, page 20). Broadcasts were in Spanish and English on medium wave 1160 kHz with 50 kW and on short wave 6000 kHz with 7.5 kW. Broadcasting times were Monday to Saturday on medium wave from 05:00-07:15 and 18:00-23:00, Sundays from 18:30-22:15. On short wave they broadcast from 08:00-10:15 (Mon-Sat) and 18:30-22:15 on Sundays (C02, page 55). Soon Radio Swan's broadcasting time was increased to around ten hours a day (A08, page 220), divided into three broadcasting blocks: morning, noon and evening/night. In the first months, there were still no guidelines for the programme content of the propaganda broadcasts. It was not until the beginning of August 1960 that the programmes were placed under the theme: "The Revolution Betrayed" (A08, page 218). CIA agent Bob Wilkinson was responsible for the operational running of the station as programme director. He held this post until Radio Americas went off the air with an annual salary of about $14,000. He was assisted by Orlando Alvarez with an annual salary of about $10,000. Alvarez was the owner of the two Cuban stations CMCH and COBH (Radio Cadena Habana) (C08, page 29) until they were taken over by Fidel Castro.

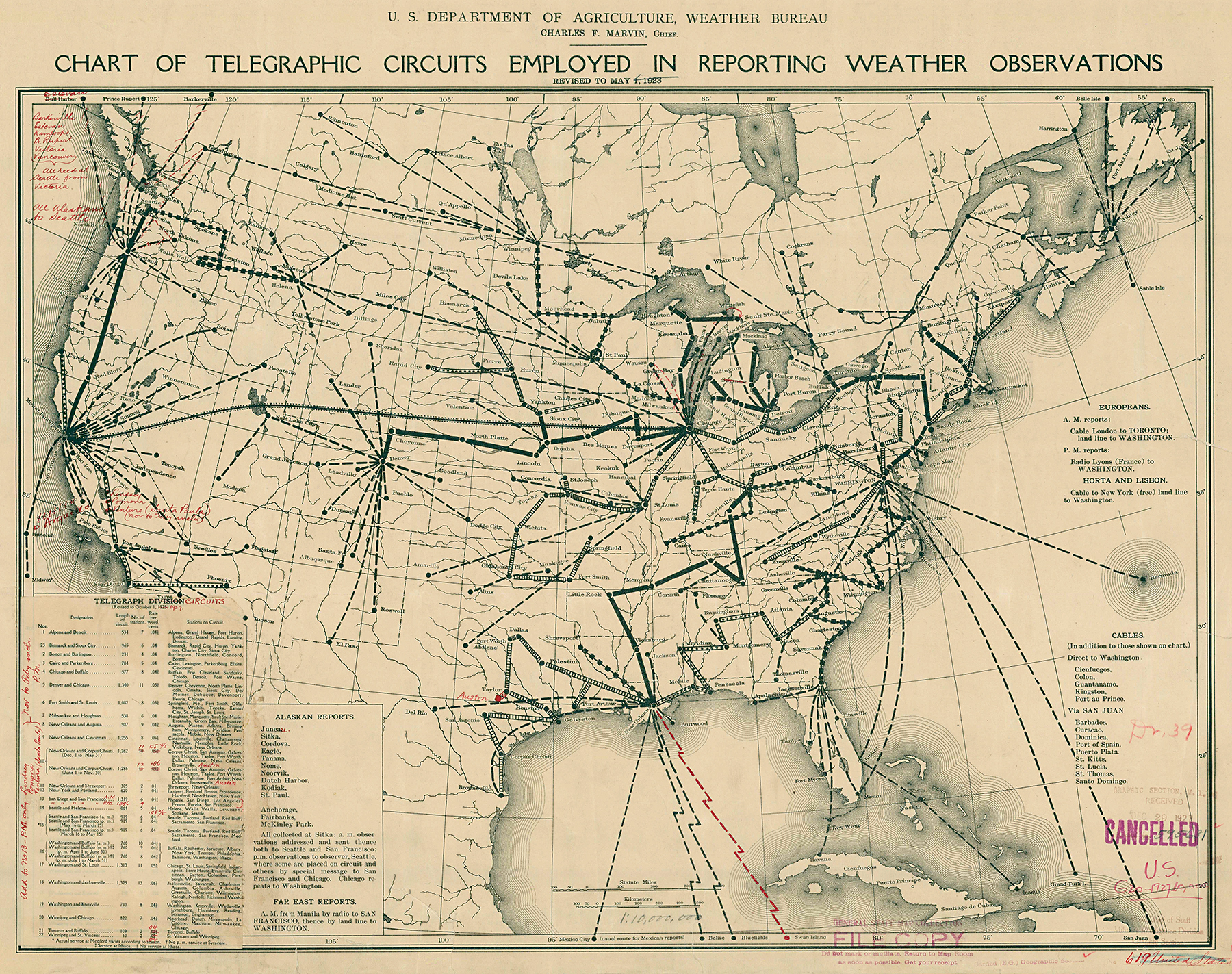

In the beginning, there was no Spanish-speaking announcer on the island who could have responded to current events. For the time being, Radio Swan only broadcast programmes that were flown in twice a week from Miami (E02, page78). The news came from New York, produced by Radio Press International (RPI), a subsidiary of station WMCA. The English news was spoken by various RPI staff. Luis Tangara, a well-known Argentinian radio personality, was used for the Spanish-language news. The news were transmitted daily via a commercial radio link to the Swan Islands. RCA transmitters on Long Island on 18910 kHz and 20820 kHz were used for this (C04, page 5).

While the entertainment programme was purchased from PAN American Broadcasting (A22, page 8), the propaganda programmes were in-house productions or originated from Cuban exiles who had organised themselves (mainly in Miami) into various groups. These groups, in turn, were largely funded by the CIA and were largely dependent on this support to carry out their activities (A22, page 3 and C21, page 7). In order to maintain the cover as a commercial station, these groups had to buy airtime from Radio Swan (A11, page 131). The recording studios for the propaganda broadcasts were located in Miami (C21, page 7).

Walter S. Lemmon and WRUL

Even before Radio Swan started broadcasting, many stations in the Caribbean region were broadcasting anti-Castro programmes created by Cuban exiles. WRUL from Boston joined them in April 1960 (C18, page 17) and allowed Radio Swan to re-broadcasts its programmes in September 1960. Walter S. Lemmon, WRUL founder and president, was also the owner of Pan American Broadcasting (C18, page 18) and thus responsible for marketing Radio Swan's airtime. This is why Radio Swan had such potent advertisers as Kleenex, Philip Morris Co. and others shortly after it started broadcasting (C04, page 7). Religious groups (The World Tomorrow, Radio Bible Class) also hired airtime from Radio Swan (C07, page 99 – D13, D14). Between October 1960 (C30, page 7) and December 1962 (C32, page 19), "The World Tomorrow" listed its broadcasts on Radio Swan/Americas in the monthly magazine "The Plain Truth".

Even before Radio Swan started broadcasting, many stations in the Caribbean region were broadcasting anti-Castro programmes created by Cuban exiles. WRUL from Boston joined them in April 1960 (C18, page 17) and allowed Radio Swan to re-broadcasts its programmes in September 1960. Walter S. Lemmon, WRUL founder and president, was also the owner of Pan American Broadcasting (C18, page 18) and thus responsible for marketing Radio Swan's airtime. This is why Radio Swan had such potent advertisers as Kleenex, Philip Morris Co. and others shortly after it started broadcasting (C04, page 7). Religious groups (The World Tomorrow, Radio Bible Class) also hired airtime from Radio Swan (C07, page 99 – D13, D14). Between October 1960 (C30, page 7) and December 1962 (C32, page 19), "The World Tomorrow" listed its broadcasts on Radio Swan/Americas in the monthly magazine "The Plain Truth".

In addition to the stations in the Caribbean region, other US stations in Miami (WGBS and WMIE), Key West (WKWF) and in Boston (WRUL) (A02, page 4 to 5 and C21, page 7) were also part of the propaganda offensive, broadcasting the programmes produced for Radio Swan by Cuban exiles in Miami. In total, the anti-Castro programmes were broadcast by seven other stations in addition to Radio Swan (A11, page 6). Several months before the Bay of Pigs invasion, CIA-backed propaganda broadcasts for all stations added up to 18 hours a day on medium wave and 16 hours a day on shortwave. During the invasion (April 17, 1961) and in the days after, the daily hours increased to 55 for medium wave and 26 on short wave (A03, page 3). Radio Swan was broadcasting around the clock during the invasion (D04, page 7).

As Fidel Castro began to consolidate his control over Cuba in the first two years after the 1959 revolution, he became increasingly concerned that the morale of the Cuban people might be sabotaged by foreign radio broadcasts. In particular, he saw Radio Swan's broadcasts as an attempt by the US to fight the Cuban revolution (B02, page 5). Fidel Castro even expressed his displeasure with Radio Swan in his speech to the United Nations on September 26, 1960 (C02, page 52). At 269 minutes, this was also the longest speech ever given in a UN plenary session.

Jamming

Within days of Radio Swan going on the air, Cuba had activated a jamming station, but it was only able to effectively suppress Radio Swan's reception in the capital Havana (A13, page 2).Cuba reacted with its own propaganda activities directed against the USA. At the end of October 1960, "La Voz de INRA" or "The Voice of INRA" (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria - National Institute for Agrarian Reform) went on the air on 1160 kHz (C02, page 53). INRA was subsequently expanded into a network with several MW and one SW station (C02, page 54). But to be heard throughout the Americas and world-wide, Cuba needed a more powerful transmitter. Around mid-March 1961, the first 100 kW transmitter was operational. Radio Havana Cuba officially began broadcasting on May 1, 1961 (D11, page 4 und B02, page 8). Other new or already existing transmitters were used by Cuba for "jamming" various stations. In mid-1967, up to ten jammers from Cuba were active in the 1155 kHz to 1165 kHz range (C10, page 42). In addition to Radio Americas, stations on the US mainland were also affected - but this is rarely mentioned in CIA documents.

Within days of Radio Swan going on the air, Cuba had activated a jamming station, but it was only able to effectively suppress Radio Swan's reception in the capital Havana (A13, page 2).Cuba reacted with its own propaganda activities directed against the USA. At the end of October 1960, "La Voz de INRA" or "The Voice of INRA" (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria - National Institute for Agrarian Reform) went on the air on 1160 kHz (C02, page 53). INRA was subsequently expanded into a network with several MW and one SW station (C02, page 54). But to be heard throughout the Americas and world-wide, Cuba needed a more powerful transmitter. Around mid-March 1961, the first 100 kW transmitter was operational. Radio Havana Cuba officially began broadcasting on May 1, 1961 (D11, page 4 und B02, page 8). Other new or already existing transmitters were used by Cuba for "jamming" various stations. In mid-1967, up to ten jammers from Cuba were active in the 1155 kHz to 1165 kHz range (C10, page 42). In addition to Radio Americas, stations on the US mainland were also affected - but this is rarely mentioned in CIA documents.

The USIA (United States Information Agency) informed the CIA as early as February 16, 1962 that the VOA and FBIS (Foreign Broadcast Information Service) had detected jamming from Cuba, with significant implications for Radio Americas, WGBS and other stations (A14). In a letter dated September 11, 1962, USIA reported that Cuba was further expanding its jamming system (A18, page 5).

The CIA's formerly secret documents claim that Radio Swan received dozens of letters from all parts of Cuba (A13, page 2). Typical of the overestimation of the propaganda effect of Radio Swan is the fact that the CIA ignored a survey of the Cuban population that it had commissioned itself. The result of this survey from August 1960 was that the overwhelming majority of Cubans viewed the Castro revolution positively. Only about 30% of the respondents answered with more or less critical comments (A08, page 223). The CIA also tried to justify the expense of Radio Swan with an operation in March 1961 to determine the extent of listening coverage (A13, page 2). All listeners who wrote to the station were promised a simple ballpoint pen. Almost 3000 letters were received from 26 countries. A significant amount of the mail came from Cuba, according to the CIA. These listener letters were considered an act of resistance against the regime because of the controls in Cuba. However, the published documents do not contain any figures on the actual number of listener letters received from Cuba. A document from 1962 or 1963 (A22, page 8) reports that most of the listeners' letters did not come from Cuba but from other Caribbean countries. Non-CIA sources even suggested that Radio Swan was listened to more for entertainment than to help shape political opinion. For factual information, Cubans preferred to tune in to the VOA, which had expanded its Spanish programmes on shortwave from about mid-1960 (B02, page 24). There were several meetings between David Atlee Phillips (CIA Chief of the Western Hemisphere Division) and VOA Director Henry Loomis to agree on programme content. While Radio Swan broadcast shrill and intrusive propaganda, VOA was responsible for more subdued allegations against Castro (A03 and C21, page 7). It was not uncommon for Radio Swan to broadcast deliberate lies to turn the Cuban people against Fidel Castro. In the programme "National Liberation Hour" of October 26, 1960, for example, it was claimed that a law would soon come into force in Cuba to intern and indoctrinate all children between the ages of 5 and 18 (B06).

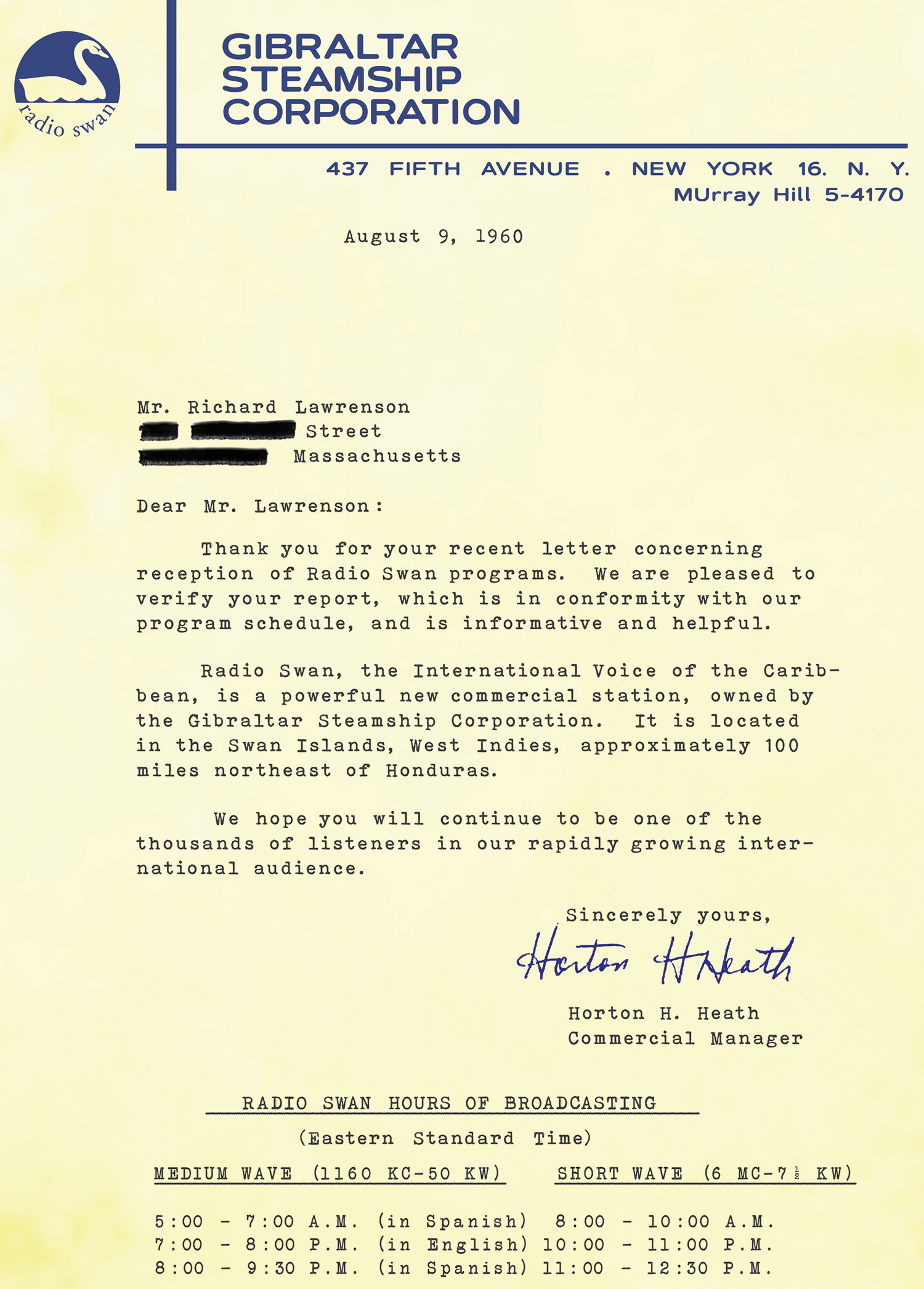

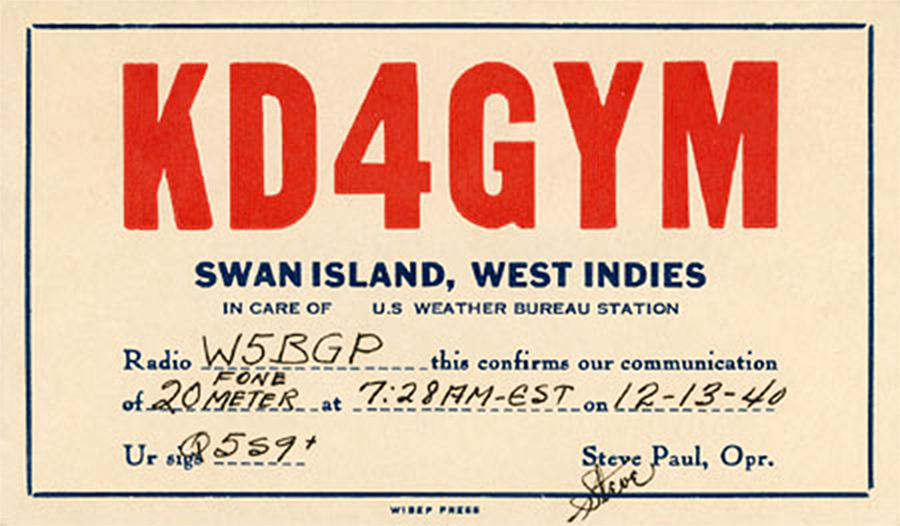

Radio Swan reliably confirmed reception reports with a QSL letter

A rare QSL letter by Radio Swan in Spanish

Bay of Pigs

By the late 1960s, Radio Swan began to lose credibility and reputation. This was due to the programmes produced by the various Cuban exile groups, which often had very different objectives. They mostly dealt with their own problems without addressing the problems of the listeners in Cuba. It happened again and again that groups wanted to distinguish themselves through sensational, bizarre false reports (A13, page 2). When efforts to establish proper control failed, the Radio Swan management informed the various Cuban exile groups in a letter dated March 27, 1961 that their programmes were no longer needed (A11, page 133). However, the CIA was also concerned to gain full control of the programmes a few weeks before the Bay of Pigs landing (A11, page 106 and page 121). The station now described itself as supporting those fighting Castro in Cuba and began transmitting psychological warfare information related to Operation Pluto (Bay of Pigs landing, April 17-19, 1961). Before and during the Bay of Pigs landing, information was broadcast as tactical support for the mercenaries and counterrevolutionary organisations in Cuba (A11, page 134).

By the late 1960s, Radio Swan began to lose credibility and reputation. This was due to the programmes produced by the various Cuban exile groups, which often had very different objectives. They mostly dealt with their own problems without addressing the problems of the listeners in Cuba. It happened again and again that groups wanted to distinguish themselves through sensational, bizarre false reports (A13, page 2). When efforts to establish proper control failed, the Radio Swan management informed the various Cuban exile groups in a letter dated March 27, 1961 that their programmes were no longer needed (A11, page 133). However, the CIA was also concerned to gain full control of the programmes a few weeks before the Bay of Pigs landing (A11, page 106 and page 121). The station now described itself as supporting those fighting Castro in Cuba and began transmitting psychological warfare information related to Operation Pluto (Bay of Pigs landing, April 17-19, 1961). Before and during the Bay of Pigs landing, information was broadcast as tactical support for the mercenaries and counterrevolutionary organisations in Cuba (A11, page 134).

To reassure the invasion troops who had set sail on April 14, 1961, Radio Swan carried the news of bombing raids on the Cuban air force on the morning of April 15, 1961. However, the approximately 1,300 men on the five invasion ships were not told that the bombing raids had partially failed and that Fidel Castro still had operational military aircraft (C27, page 20). On Sunday evening (April 16, 1961), Radio Swan's hitherto passive role changed dramatically to active participation in the invasion. Several times Radio Swan repeated the announcement: "Alert! Alert! Look well at the rainbow. The fish will rise soon. Chico is in the house. Visit him. The sky is blue. ... The fish will not take much time to rise. The fish is red" (C13, page 67 – C27, page 21 - D10 and B06) This was meant to indicate the beginning of the Bay of Pigs invasion. Later it turned out that neither the landing troops already on land nor those who had stayed behind on the ships received this message. The underground troops in Havana heard this message, but since they had not been informed of the meaning of this code, nor of the imminent invasion, they did not know what to do (A11, page 116 and C27, page 21). Thus, the uprising that was actually planned to support the landing troops did not take place. Nonetheless, the CIA-controlled programmes on Radio Swan reported on the patriotic commitment of the freedom fighters and the imminent defeat of Fidel Castro. Around 5:15 on the morning of April 17, 1961, Radio Swan was reporting a large-scale uprising across the Cuban island. When it became clear that all was not going according to plan and the invading forces were surrounded by the Cuban military, Radio Swan called for the Cuban military to revolt against Fidel Castro early in the morning at 3:44 (Tuesday April 18, 1961). This was followed by further calls for internal sabotage and coded messages (C27, page 23).

By the afternoon of April 19, 1961 at the latest, it was clear that the invasion had failed and the majority of revolutionary fighters had been captured. Nevertheless, Radio Swan continued to broadcast tactical information and mysterious orders to (non-existent) battalions (A11, page 66). On April 22, 1961, Radio Swan even reported that more reinforcement troops had landed in Cuba (C27, page 24 and B02, page 7).In retrospect, it turned out that this was a completely wrong view of the facts. During the invasion Radio Swan had been broadcasting around the clock (B02, page 7), within a week it returned to the normal broadcasting schedule (A23).

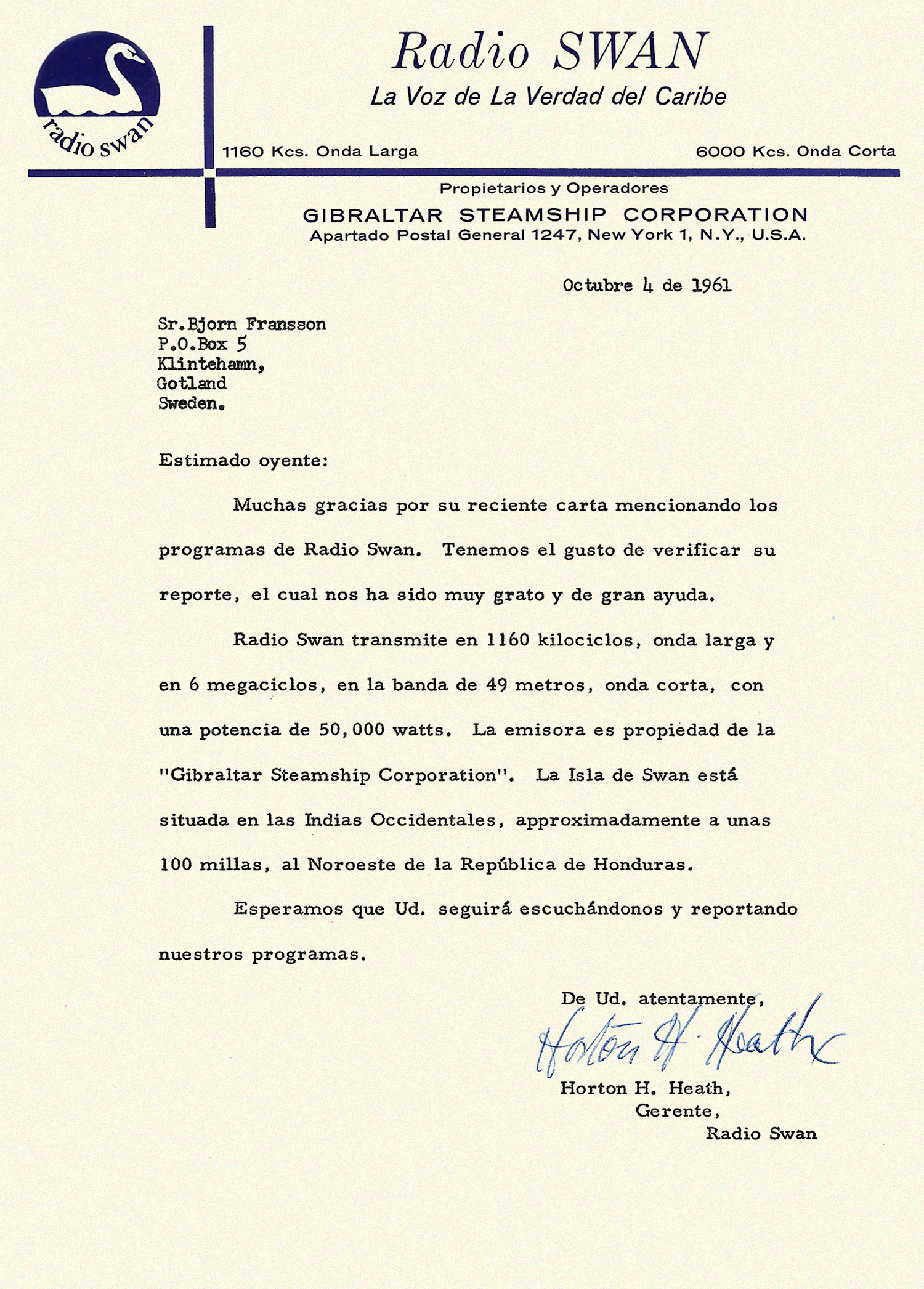

Radio Americas

The programmes no longer called for an uprising against the Cuban government, but only broadcast propaganda directed against Fidel Castro. The news embedded in the entertainment programme offered reports of counter-revolutionary activities, but avoided comments that could be interpreted as incitement to rebellion (B06). The station was now broadcasting on short and medium wave according to the following transmission schedule: 5 am to 8 am, 12:30 pm to 2 pm and from 6 pm to 12:15 am (A13, page 5). Radio Swan reliably confirmed reception reports with a QSL letter signed by Horton H. Heath. After the station name was changed to Radio Americas in November 1961 (the station was now owned by Vanguard Service), there were no acknowledgments for reception reports for several months. It was not until September 1962 that Radio Americas began sending out a colorful QSL card showing the station's location in the Caribbean (C27, page 26). The cards were initially signed by Agnes Shirley or C. Stanley, and later by other staff members as well. The ubiquitous Horton Heath disappeared, Roger Butts (probably a new identity of Horton Heath – C27, page 53) was now listed as the new station manager. In an interview Roger Butts explained that Vanguard Service had leased the transmitters from the Gibraltar Steamship Co. (C27, page 27). According to Roger Butts, the running costs of the station were raised by sponsors. From today's perspective, it is of course clear that this "sponsor" was the CIA.

The programmes no longer called for an uprising against the Cuban government, but only broadcast propaganda directed against Fidel Castro. The news embedded in the entertainment programme offered reports of counter-revolutionary activities, but avoided comments that could be interpreted as incitement to rebellion (B06). The station was now broadcasting on short and medium wave according to the following transmission schedule: 5 am to 8 am, 12:30 pm to 2 pm and from 6 pm to 12:15 am (A13, page 5). Radio Swan reliably confirmed reception reports with a QSL letter signed by Horton H. Heath. After the station name was changed to Radio Americas in November 1961 (the station was now owned by Vanguard Service), there were no acknowledgments for reception reports for several months. It was not until September 1962 that Radio Americas began sending out a colorful QSL card showing the station's location in the Caribbean (C27, page 26). The cards were initially signed by Agnes Shirley or C. Stanley, and later by other staff members as well. The ubiquitous Horton Heath disappeared, Roger Butts (probably a new identity of Horton Heath – C27, page 53) was now listed as the new station manager. In an interview Roger Butts explained that Vanguard Service had leased the transmitters from the Gibraltar Steamship Co. (C27, page 27). According to Roger Butts, the running costs of the station were raised by sponsors. From today's perspective, it is of course clear that this "sponsor" was the CIA.

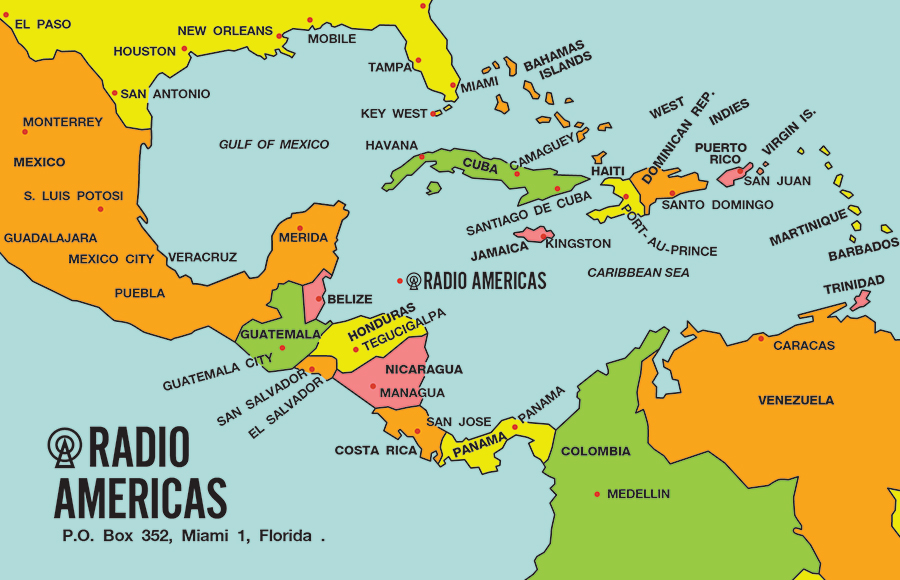

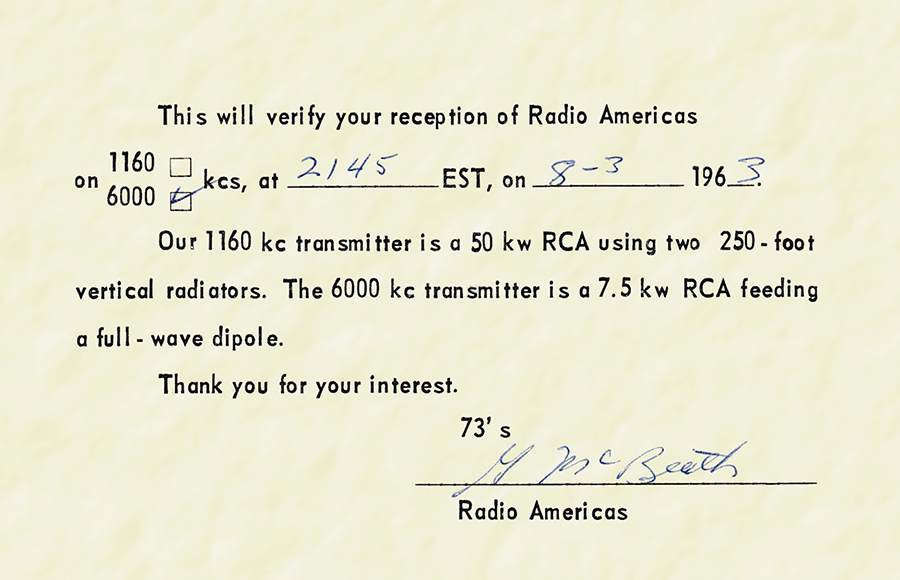

Beginning in September 1962, Radio Americas sent out this colorful QSL card.

The flip side contained detailed information about the transmitters used.

By now, Radio Americas had a team of more than 30 people who put together almost the entire programme in Miami and recorded it on tape. Some of the staff came from station CMQ (B06), which was closed by Fidel Castro on September 13, 1960. The recordings were made in a small studio in Coral Gables, Florida, 101 Madeira Avenue and at Continental Sound Recording Studios, 2020 N.W. 7th St. Miami (C08, page 29). The tapes were flown to Swan Island once or twice a week by plane (a single-engine Piper Comanche owned by Radio Americas). On the island itself, there were now four Spanish-language newscasters and an American announcer. The news broadcast every half hour was compiled from AP and UPI material (obtained by teletype via shortwave). A few shows were also recorded directly on Swan Island from the WNYW shortwave station in Scituate, Mass (Radio New York Worldwide - formerly WRUL) for later re-broadcasting (C08, page 29).

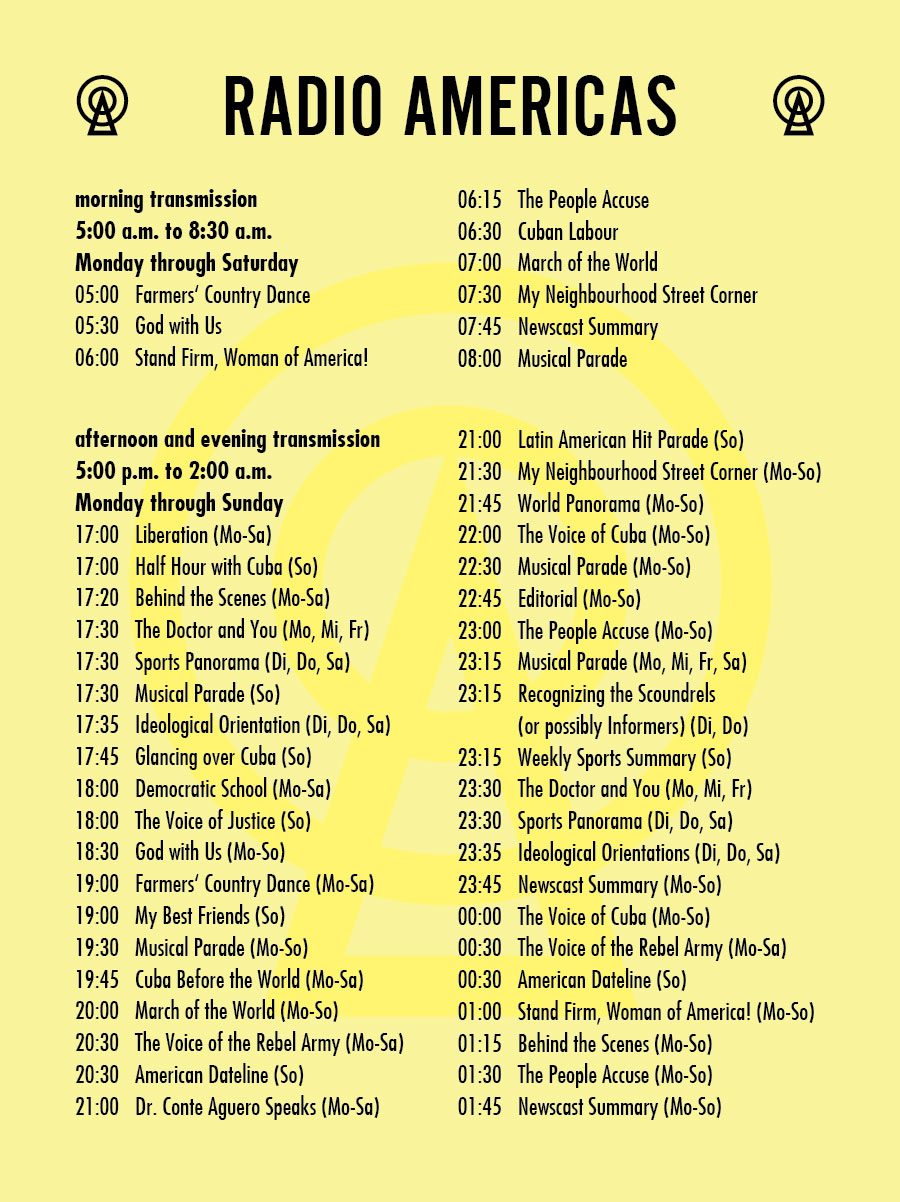

Programme schedule from March 1965 (translated from Spanish)

Proportions of the programme elements:

news, commentary, propaganda = 71%

music = 14%

health = 6%

religion = 8%

sports = 1%

Propaganda without success

A programme schedule from March 1965 shows how far the now almost exclusively Spanish-language programme had deviated from its original claim to be an "American commercial station" (C27, page 28). On a weekly average, there was only around 14% music, health and religion occupied 6 and just under 8 per cent of airtime respectively. The share of sports programmes was even less than one per cent. More than two-thirds of the broadcasting time was thus filled with news, commentary, speeches and propaganda.

A programme schedule from March 1965 shows how far the now almost exclusively Spanish-language programme had deviated from its original claim to be an "American commercial station" (C27, page 28). On a weekly average, there was only around 14% music, health and religion occupied 6 and just under 8 per cent of airtime respectively. The share of sports programmes was even less than one per cent. More than two-thirds of the broadcasting time was thus filled with news, commentary, speeches and propaganda.

In general, the Cubans are cheerful people with a light-hearted attitude to life. Under Castro they were subjected to endless, persistent confrontation with the policies and propaganda of their own government. It is therefore not surprising, that the average Cuban had little interest in spending his free time being bombarded with propaganda by Radio Americas (whose reception was banned in Cuba anyway – C14, page 17) as well. He preferred to tune in to the Spanish entertainment programme of the Voice of America. On the radio dial the VOA station from Marathon, Florida (the forerunner of Radio Marti) was almost the immediate neighbour to Radio Americas on 1180 kHz (C14, page 19). The situation in Central and South America was different. There were certainly eager listeners to Radio Americas (C31, page 2). The efforts made by the USA in the fight against Castro gave the impression that Castro must be even more important for Latin America than he actually appeared to be (C14, page 19).

CIA propaganda broadcasts to Cuba reached their peak in early 1965, with expenditures of $1.5 million. The Cuban Freedom Committee, as a cover for Radio Free Cuba, broadcast 77 hours a week via stations in Miami, Key West and New Orleans (A21, page 281). Broadcasts by Radio Americas and three other leased commercial stations totalled 119 hours a week (A21, page 282). Despite all these propaganda efforts to turn the Cuban people against Castro, the success of Radio Americas and other actions tended towards zero. This and the changed global political situation (US involvement in the Vietnam War from around 1964) led to the anti-Castro efforts slowly being scaled back from 1965 onwards (A21, page 288).

The budget cuts for CIA underground activities ultimately resulted in Radio Americas ceasing broadcasting on May 15, 1968 (C05). While PBSUCCESS in 1954 against Guatemala was still a success (at least from the CIA's point of view), Radio Swan/Radio Americas (as well as the CIA's entire anti-Castro actions) can arguably be called the faux pas of the century.

Radio Swan - the technology

From Eagle to Swan

It's July 4, 1950, 7:30 a.m. - the start of broadcasting by Radio Free Europe. Near Lampertheim/Germany, "Barbara", a mobile 7.5 kW shortwave transmitter of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) installed on trailers, is used for this purpose (C25, page 8 and C26, page 46). Exactly one year later, "Barbara" starts broadcasting from Portugal for a few years (C25, page 9 and D06). It is unclear whether and when "Barbara" was shipped back to the USA after it was decommissioned. Also in 1950, the CIA had two other mobile shortwave transmitters, similar to "Barbara", but with only 500 watts, in use in Greece for Radio Goryanin (B07 and B08, page 68). Whether "Barbara" or another transmitter owned by the CIA found its way to Radio Swan in the Caribbean could not be definitively clarified. As early as 1954, a transmitter on Swan Island was used by the CIA to overthrow the Guatemalan government (A21, page 282 and D02, page 117). This was probably the decisive factor in selecting this island again as a location for radio broadcasts.

It's July 4, 1950, 7:30 a.m. - the start of broadcasting by Radio Free Europe. Near Lampertheim/Germany, "Barbara", a mobile 7.5 kW shortwave transmitter of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) installed on trailers, is used for this purpose (C25, page 8 and C26, page 46). Exactly one year later, "Barbara" starts broadcasting from Portugal for a few years (C25, page 9 and D06). It is unclear whether and when "Barbara" was shipped back to the USA after it was decommissioned. Also in 1950, the CIA had two other mobile shortwave transmitters, similar to "Barbara", but with only 500 watts, in use in Greece for Radio Goryanin (B07 and B08, page 68). Whether "Barbara" or another transmitter owned by the CIA found its way to Radio Swan in the Caribbean could not be definitively clarified. As early as 1954, a transmitter on Swan Island was used by the CIA to overthrow the Guatemalan government (A21, page 282 and D02, page 117). This was probably the decisive factor in selecting this island again as a location for radio broadcasts.

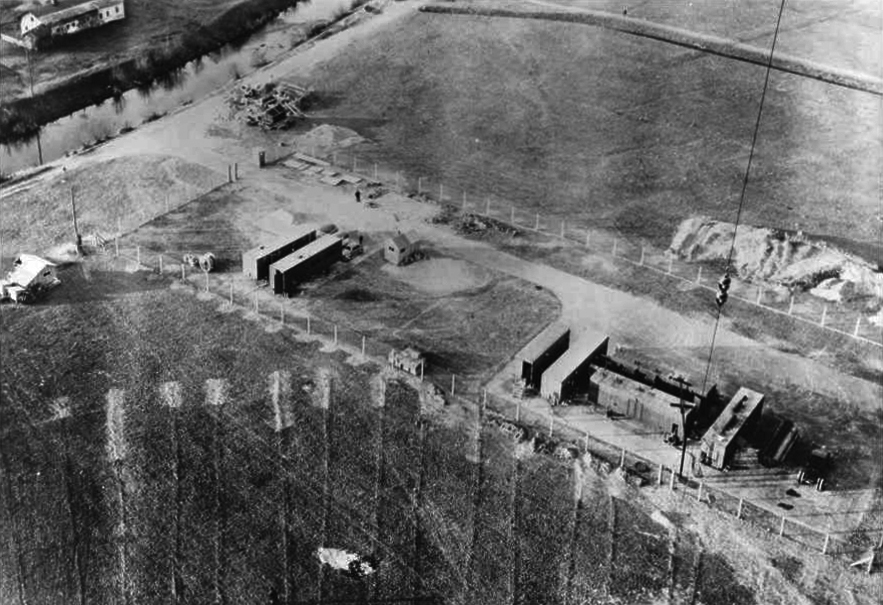

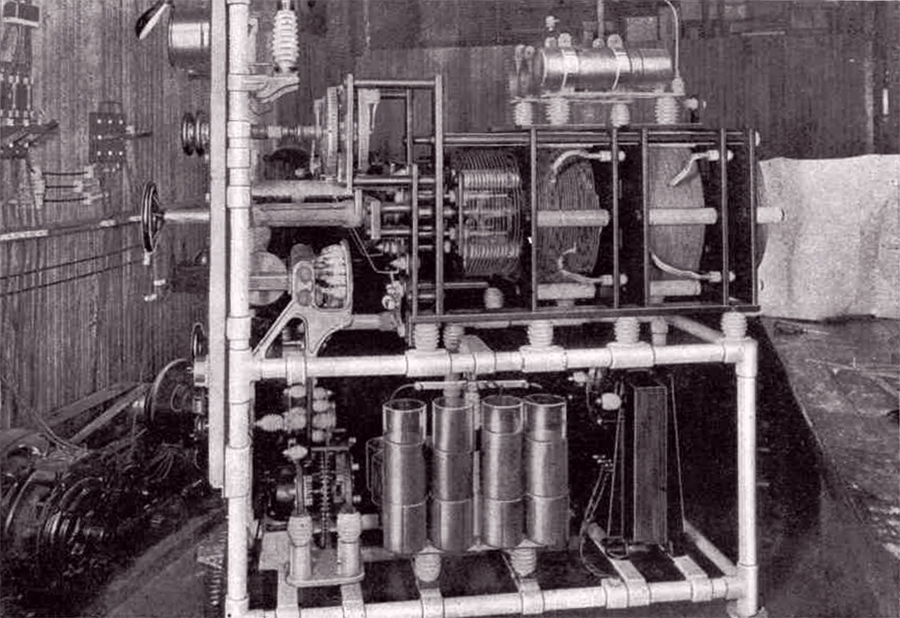

In the case of "Eagle", another mobile transmitter on trailers (C20, page 8 and D02, page 130) the situation is much clearer. This 50-kW medium wave transmitter was used from 1953 onwards in the Cham area (Bavaria, Upper Palatinate) to support other RFE transmitters (C26, page 50 – C28 and D07). However, only one omnidirectional antenna was available there, there was interference and jamming, so the transmitter could not be used very successfully. Finally, a flood in July 1954 ended the first brief career of "Eagle". The transmitter was transported to Bremerhaven and stored there (C28). It most likely went from there to storage facilities at Bush Terminal, Brooklyn (A11, page 131). Other US transmitters were also stored there, some of them for later use by the VOA (A25, page 1).

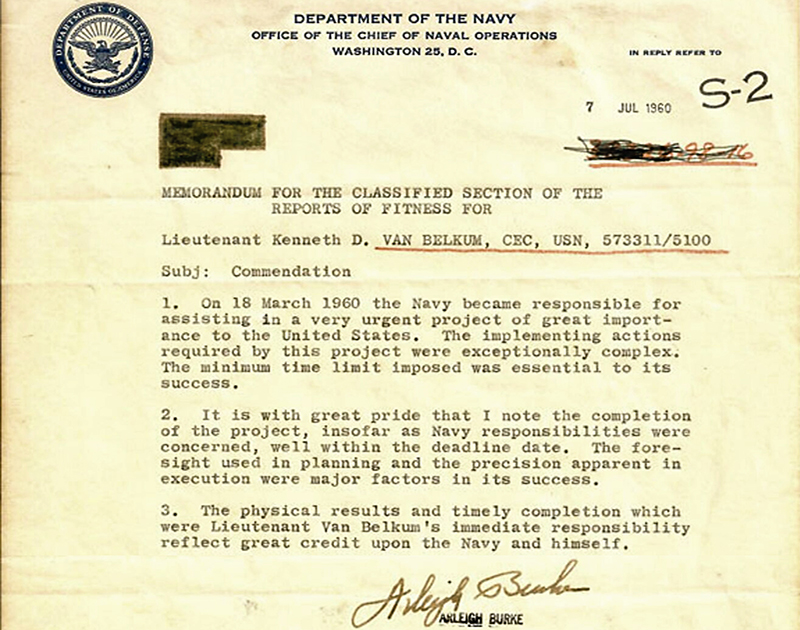

Busy "sea" bees

On March 18, 1960, just one day after President Eisenhower approved the anti-Castro programme, the US Navy's Construction Battalion Atlantic (CBLANT) was commissioned to build a radio station on Swan Island. At that time, Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 6 (NMCB Six) with 130 Navy Seabees (sea bees, derived from the abbreviation CB for Construction Battalion) was at the Naval Construction Battalion Center (NCBC) Davisville, Rhode Island to prepare for a mission in Bermuda. NMCB Six was ordered to prioritize the Swan project over Bermuda. Within eight hours, a list of needed materials (furniture, fixtures, kitchen equipment, dishes, bedding, etc.) had been compiled. Much was available in the warehouses of the naval base (D03). Materials not available on site probably came from the naval depot at Bush Terminal, Brooklyn, some 300 kilometres away. The first trucks arrived in Davisville just ten hours after the order was placed. Within four days, two LST's (tank landing ships) arrived at the Rhode Island base and were loaded with over 80,000 kg of construction material and equipment. The first LST arrived at Swan Island about a week later. Within 20 days, two aerial masts were erected, a makeshift runway had been levelled and buildings constructed. The expenditure of this operation was reported as a little under $225,000 (A08, page 213).

On March 18, 1960, just one day after President Eisenhower approved the anti-Castro programme, the US Navy's Construction Battalion Atlantic (CBLANT) was commissioned to build a radio station on Swan Island. At that time, Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 6 (NMCB Six) with 130 Navy Seabees (sea bees, derived from the abbreviation CB for Construction Battalion) was at the Naval Construction Battalion Center (NCBC) Davisville, Rhode Island to prepare for a mission in Bermuda. NMCB Six was ordered to prioritize the Swan project over Bermuda. Within eight hours, a list of needed materials (furniture, fixtures, kitchen equipment, dishes, bedding, etc.) had been compiled. Much was available in the warehouses of the naval base (D03). Materials not available on site probably came from the naval depot at Bush Terminal, Brooklyn, some 300 kilometres away. The first trucks arrived in Davisville just ten hours after the order was placed. Within four days, two LST's (tank landing ships) arrived at the Rhode Island base and were loaded with over 80,000 kg of construction material and equipment. The first LST arrived at Swan Island about a week later. Within 20 days, two aerial masts were erected, a makeshift runway had been levelled and buildings constructed. The expenditure of this operation was reported as a little under $225,000 (A08, page 213).

After the two masts were erected, a CIA representative had a black trailer towed from the second LST. A day later, on May 17, 1960, Radio Swan went on the air. This detailed description of the work from Navy documents (D03 und C37) indicates that the shortwave transmissions did not go on the air at the same time as the medium wave. The first reception reports of Radio Swan on shortwave date from August 1960 (D04, page 1 and page 20). To complete the buildings and runway, the Seabees remained on Swan for a few more weeks.

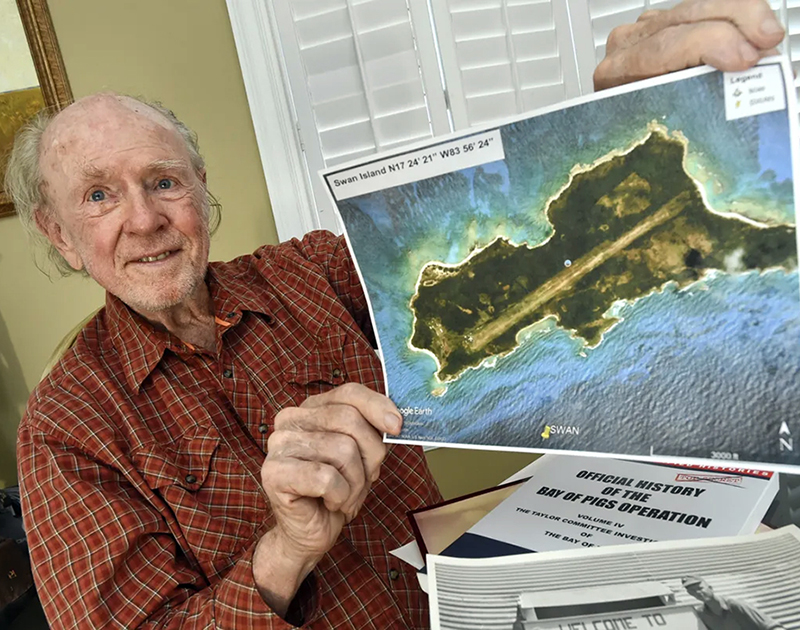

After the secrecy for Kenneth van Belkum's award about his involvement in setting up Radio Swan was lifted, the local press reported extensively on his experiences. (Photo: Northwest Florida Daily News)

Lieutenant Kenneth van Belkum received an award from the highest authority for his work in establishing Radio Swan. But this award was also kept secret, so that Kenneth only found out about it when he reached retirement age. (Seabee Magazine)

Lieutenant Kenneth D. van Belkum must have done such an outstanding job with his Seabees that Navy Admiral Arleigh Burke bestowed a very rare commendation at the time. However, the entire naval operation - and thus also the commendation - was so secret that Kenneth van Belkum only learned about it when he had retired (C37).

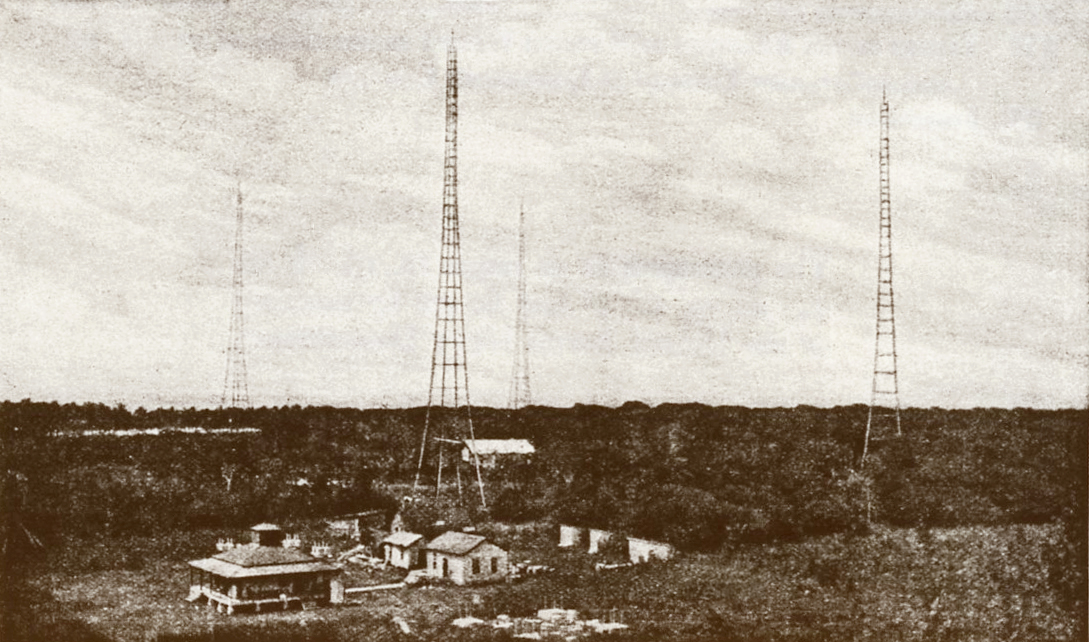

Approaching Swan Island around 1961. The buildings and antennas in the middle of the picture show the living and working quarters of the weather service and the aeronautical radio station. To the right, older buildings of the United Fruit Company (built from around 1910) that are no longer usable. Above right, next to the runway, Radio Swan's residential and studio buildings. (Archive Tom Sundstrom, W2XQ)

Detailed view of the inhabited part of Swan Island. At top left, the living quarters of the Honduran soldiers, including the mostly dilapidated area of the former United Fruit Company buildings. On the right, the remains of the Radio Swan/Americas residential and studio complex. (Google Earth, April 13, 2008)

Station description

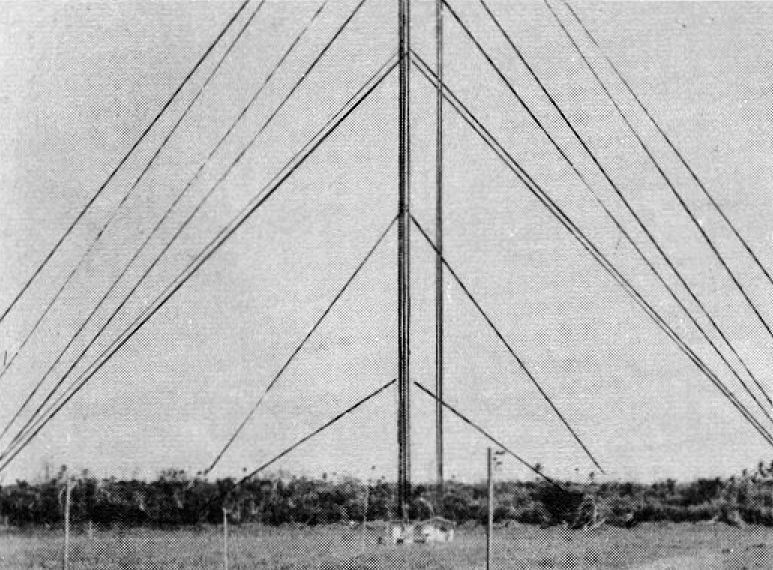

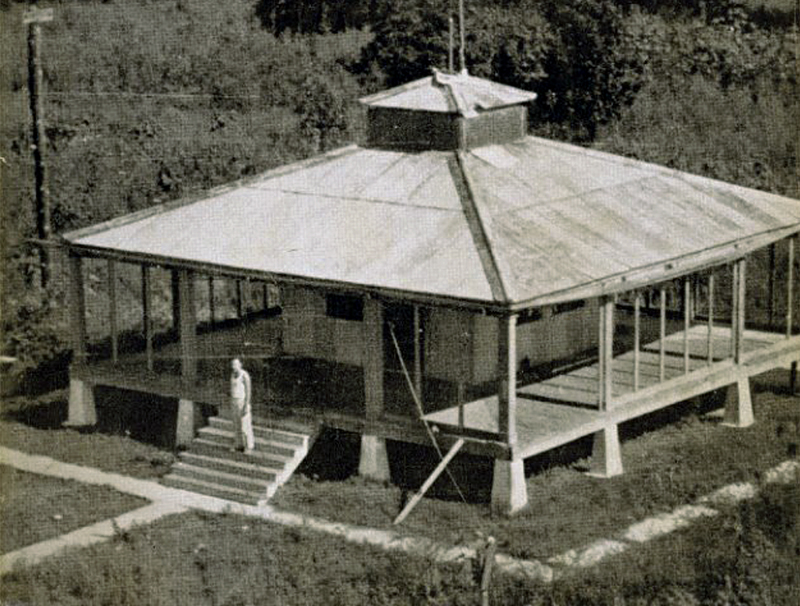

The two medium wave aerial masts (vertical radiators) had a height of 74 metres each. An antenna modification carried out at the beginning of 1961 (phase feed with preference for the eastern mast) made it possible to achieve a directional effect towards Cuba (A11, page 48 – C09, page 51 and C15, page 20). This also improved reception on the US mainland (C03, page 77). A few hundred metres to the west were several small masts (between which a full-wave dipole was stretched) (C15, page 20 and C17, page 16) which were used for short-wave transmissions. The trailer with the transmitters were placed on concrete bases under a protective roof.

The two medium wave aerial masts (vertical radiators) had a height of 74 metres each. An antenna modification carried out at the beginning of 1961 (phase feed with preference for the eastern mast) made it possible to achieve a directional effect towards Cuba (A11, page 48 – C09, page 51 and C15, page 20). This also improved reception on the US mainland (C03, page 77). A few hundred metres to the west were several small masts (between which a full-wave dipole was stretched) (C15, page 20 and C17, page 16) which were used for short-wave transmissions. The trailer with the transmitters were placed on concrete bases under a protective roof.

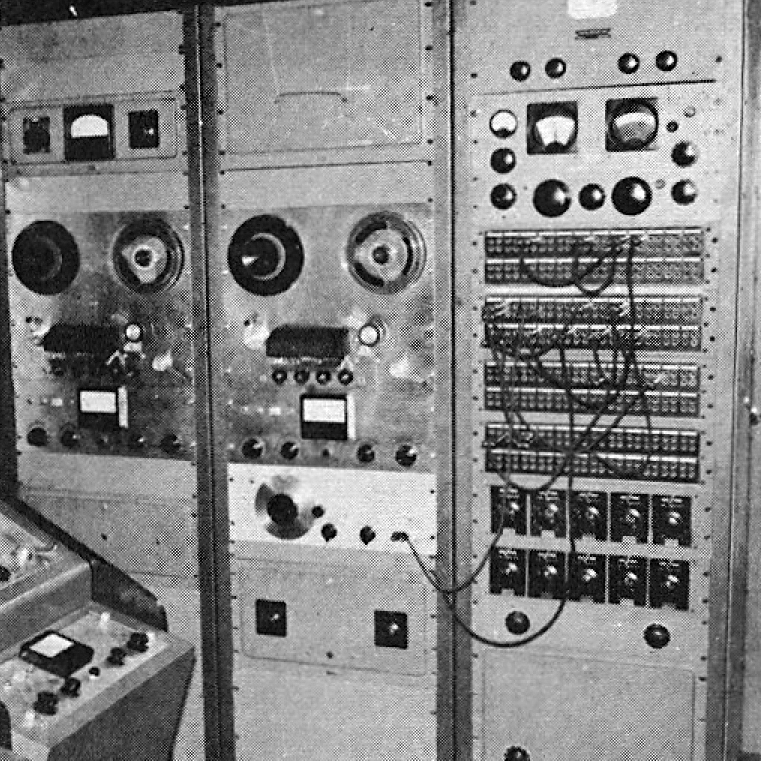

Right next to the transmitters, two huge diesel generators were housed in a separate building. They supplied the transmitters and other equipment with power. Two employees alone were just responsible for the maintenance of the generators and the vehicles (Harvester Scout 4WD). Six technicians ensured the smooth operation of the transmitters. (C15, page 21). A station manager completed the Philco service team of nine people.

On the left the transmission trailers under a canopy, in front of them two Harvester Scout SUVs. In the building behind there are two diesel generators. (Photo: Tom Kneitel, February 1968) (colored later)

View from the southeast towards Radio Swan's AM antenna with hurricane rated guying. The little house with the tuning unit can be seen under the front mast. (CIA press photo 1961)

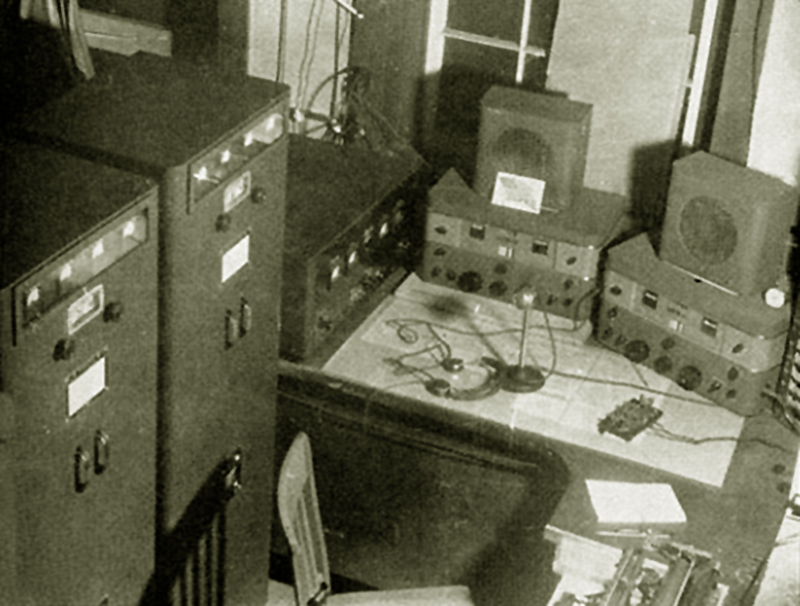

In July 1960, Radio Swan had 24 employees on the island, all but nine CIA personnel (A08, page 217). These nine were technicians from the Logistics Service Corporation of Philadelphia (a subsidiary of Philco Corporation) and were responsible for all technical aspects (transmitter, power supply, antennas) of the station (A21, page 283). They were not aware that their employer had been contracted by the CIA for the maintenance work. The monthly cost of broadcasting on Swan was about $30,000. Initially, programmes were flown in twice a week by Coastal Air Inc. (4041 NW 25th St, Miami, FL 33142) from Miami via Cozumel (Mexico) using an Aero Commander 520 built in 1952. From mid/late 1961, the station, now renamed Radio Americas, received deliveries by light aircraft only once a week (A21, page 283). In the meantime, there were also several Spanish-speaking announcers on the island (A21, page 283),so that they were not only dependent on delivered tapes. However, almost only news and station announcements were broadcast live. Therefore, only a small studio with a table and microphone was needed. Teletypewriters, receivers and tape recorders for rebroadcasting took up much more space (C15, page 20). Parts of the programmes broadcast by Radio Americas were taped by other stations for re-broadcast at a later date.

Fuel for the diesel generators, food and other heavy goods reached the island by ship from Tampa, Florida about every 10 days (C04, page 6) (another source speaks of two months - E02, page 78). The "Hamilton Brothers Steamship. Co.", which also supplied the employees of the Weather Service and the Federal Aviation Authority stationed on Swan Island, used three former Navy landing ships for the supply runs (C04, page 5).

Voice of the Escambray

During the Bay of Pigs invasion, an underground radio station "Voice of the Escambray" was also active. Allegedly, this transmitter was located in a rebel camp in the Escambray Mountains in Cuba. In fact, however, a reserve transmitter was used on Swan Island (A11, page 134 and C21, page 11). This second shortwave transmitter was probably also used to broadcast Radio Americas on 11800 kHz (parallel to 6000 kHz) starting in autumn 1962. However, the frequency 11800 kHz was given up again sometime in 1963. In the press at the time, different power ratings of 3.5 kW and 5 kW appeared for this transmitter. The shortwave frequency of 6000 kHz was also changed briefly to 6005 kHz. Radio Americas returned to 6000 kHz as early as November 1962. In order to avoid interference with American stations on 1160 kHz, the medium wave frequency was changed to 1165 kHz and shortly afterwards to 1157 kHz in March 1965 (C27, page 27).

During the Bay of Pigs invasion, an underground radio station "Voice of the Escambray" was also active. Allegedly, this transmitter was located in a rebel camp in the Escambray Mountains in Cuba. In fact, however, a reserve transmitter was used on Swan Island (A11, page 134 and C21, page 11). This second shortwave transmitter was probably also used to broadcast Radio Americas on 11800 kHz (parallel to 6000 kHz) starting in autumn 1962. However, the frequency 11800 kHz was given up again sometime in 1963. In the press at the time, different power ratings of 3.5 kW and 5 kW appeared for this transmitter. The shortwave frequency of 6000 kHz was also changed briefly to 6005 kHz. Radio Americas returned to 6000 kHz as early as November 1962. In order to avoid interference with American stations on 1160 kHz, the medium wave frequency was changed to 1165 kHz and shortly afterwards to 1157 kHz in March 1965 (C27, page 27).

The end of Radio Americas

The aging RCA shortwave transmitter broke down on September 20, 1967. Since the shortwave listeners were not the real target of Radio Americas anyway, a costly repair was not considered (C10, page 42). In February 1968 the station was heard again on shortwave (C09, page 50) (probably via the former 5 kW Escambray transmitter), but shortly thereafter the shortwave fell silent for good. Rumour has it that the shortwave transmitter went to a religious community in South Africa but was never used. The religious society CARA wanted to use a transmitter in Africa, but this was already in 1966 and it was a 1000 Watt shortwave transmitter (C12, page 51 and C16, page 38).

The aging RCA shortwave transmitter broke down on September 20, 1967. Since the shortwave listeners were not the real target of Radio Americas anyway, a costly repair was not considered (C10, page 42). In February 1968 the station was heard again on shortwave (C09, page 50) (probably via the former 5 kW Escambray transmitter), but shortly thereafter the shortwave fell silent for good. Rumour has it that the shortwave transmitter went to a religious community in South Africa but was never used. The religious society CARA wanted to use a transmitter in Africa, but this was already in 1966 and it was a 1000 Watt shortwave transmitter (C12, page 51 and C16, page 38).

After the broadcasts were discontinued in 1968 (A22, page 2), the 50-kW medium-wave transmitter is said to have been used in the Vietnam War from 1970 onwards (D05 and D06). Other reports (C26, page 51) also speak of the transmitter being transported to Vietnam but broadcasting psychological warfare programmes from an aircraft (Blue Eagle- Project Jenny). This seems unlikely, however, since Blue Eagle I had already been used in Vietnam since October 1965 (D12).The shoving of the transmitter into the sea off the coast of Swan Island as described by David Hollyer (C28) seems to be confirmed by a short sequence of images in a video from 2022 (F02). However, it is not really possible to tell whether it is in fact a sunken transmitter container. It is therefore not possible to make a definite statement about the whereabouts of the Radio Swan/Americas transmitters.

Occasionally Swan Island is visited by sailors. Edwin and Wendy Cutler were there in May 1985. They reported that the antenna masts were still standing and the station buildings were in a reasonably acceptable condition (E03). At the end of October 1998, one of the strongest storms ever recorded, Hurricane Mitch, swept across the island with wind speeds of up to 285 km/h and destroyed the transmission towers (E04, E06). However, some of the buildings of Radio Swan/Radio Americas seem to have survived Mitch. They can still be seen in a photo from 2011 (E05, page 12)). Today, only the densely overgrown bases of the antenna masts, surrounded by rusting metal parts, bear witness to the antenna masts (F02).

Radio Swan / Radio Americas station building in 1985. (Photo: Edwin and Wendy Cutler)

View of the western part of Great Swan from the northwest, in the clearing to the right of center are the buildings of the weather station and the Honduran military base. Directly below the runway there are still some Radio Swan/Americas buildings visible. (Photo: Kip Evans, 2011)

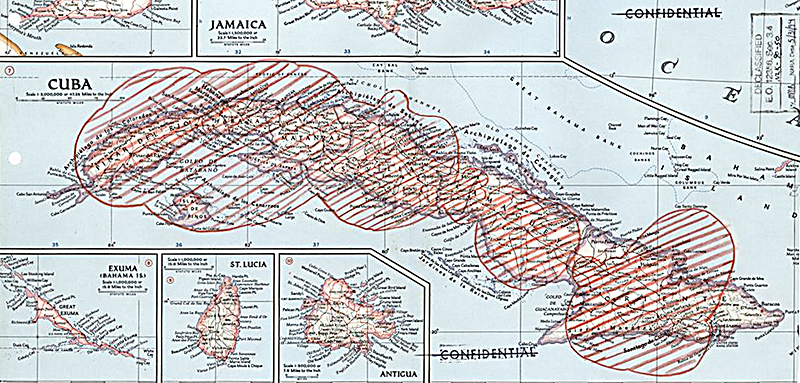

In order to find the tiny Swan Islands on a map, you have to resort to special map material. In this map section of the Defense Mapping Agency from 1977, transmission masts are still noted.

The last remnants of the antenna masts fell victim to Hurricane Mitch in 1998. Today only the base of the mast (here from a medium-wave mast) points to the broadcasting past. (Danny Germer, 2022)

Radio Swan - the listeners are puzzled

Secret operations should remain hidden!

According to "Title 50 U.S. code § 3093 (e)" (A26), clandestine operations and activities of the USA shall be conducted in such a way as to conceal CIA or United States involvement. In the case of Radio Swan/Americas (and other actions directed against Cuba at the time), this failed miserably. This is probably one of the reasons why the CIA resisted the publication of its documents from this period for a very long time (partly until 2016) (A27). But it was only through the publication of these documents that it was possible to confirm the assumptions made at the time and to prove the CIA's actual involvement in Radio Swan/Americas.

According to "Title 50 U.S. code § 3093 (e)" (A26), clandestine operations and activities of the USA shall be conducted in such a way as to conceal CIA or United States involvement. In the case of Radio Swan/Americas (and other actions directed against Cuba at the time), this failed miserably. This is probably one of the reasons why the CIA resisted the publication of its documents from this period for a very long time (partly until 2016) (A27). But it was only through the publication of these documents that it was possible to confirm the assumptions made at the time and to prove the CIA's actual involvement in Radio Swan/Americas.

At the time, the new station, which suddenly appeared practically out of nowhere, was met with astonishment and amazement by listeners (C08, page 27). The first reports about Radio Swan appeared in the DX News of the National Radio Club in June and July 1960. It was already noticed then that the FCC had not listed the station (C23, page 13 and C24, page 15). Soon, the very active American DXers discovered further inconsistencies with the station. In June 1960, the American press also began to doubt that Radio Swan was really a legitimate commercial enterprise (A06, page 11 and B02, page 6).

The owner

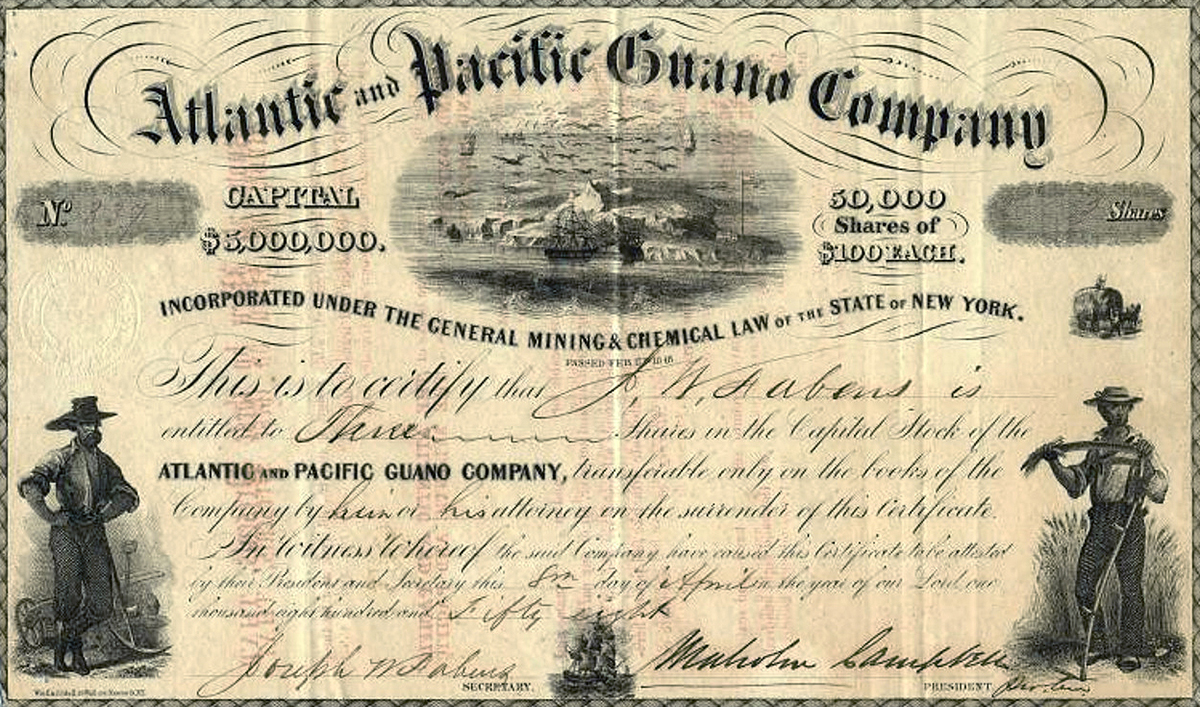

Radio Swan was owned by the Gibraltar Steamship Corporation, a CIA front company (A08, page 213 and A21, page 283), which did not own any ships. The president was Thomas Dudley Cabot, a former president of the United Fruit Company (C07, page 100 and D04, page 5) (which had several CIA operatives on its payroll) and former Director of Homeland Security at the US State Department (C04, page 7 and B02, page 6). The owner of Swan Island was believed to be a Mr Sumner Smith. He held the post of Vice President at the Gibraltar Steamship Corporation and charged (and received) rent from Radio Swan for the use of his island (A21, page 283 and C36).

Radio Swan was owned by the Gibraltar Steamship Corporation, a CIA front company (A08, page 213 and A21, page 283), which did not own any ships. The president was Thomas Dudley Cabot, a former president of the United Fruit Company (C07, page 100 and D04, page 5) (which had several CIA operatives on its payroll) and former Director of Homeland Security at the US State Department (C04, page 7 and B02, page 6). The owner of Swan Island was believed to be a Mr Sumner Smith. He held the post of Vice President at the Gibraltar Steamship Corporation and charged (and received) rent from Radio Swan for the use of his island (A21, page 283 and C36).

The Gibraltar Steamship Co. changed its address several times. First came the P.O. Box 1247, G.P.O., New York (C02, page 55), followed by an address in Manhattan: 437 Fifth Avenue - both locations where there were no Radio Swan employees. Nevertheless, reception reports were answered quickly and reliably (D04, page 2) – signed by Mr. Horton H. Heath. The very first QSL letters, however, had a slightly different signatory: R. H. H. Heath. In the 1950s, a certain Roger H. H. Heath worked for the US Air Force Intelligence Service (C27, page 53). The assumption that this was one and the same CIA employee seems obvious.

Radio Swan also sometimes used the address 29 Broadway, New York 6. It led to a law firm. Richard S. Greenlee, a partner in this firm, worked for the Gibraltar Steamship Co. as a corporate lawyer. And finally, 18 East 50th Street was also in use by Radio Swan (C04, page 7). This was an unused part of the Radio Press International offices (RPI).

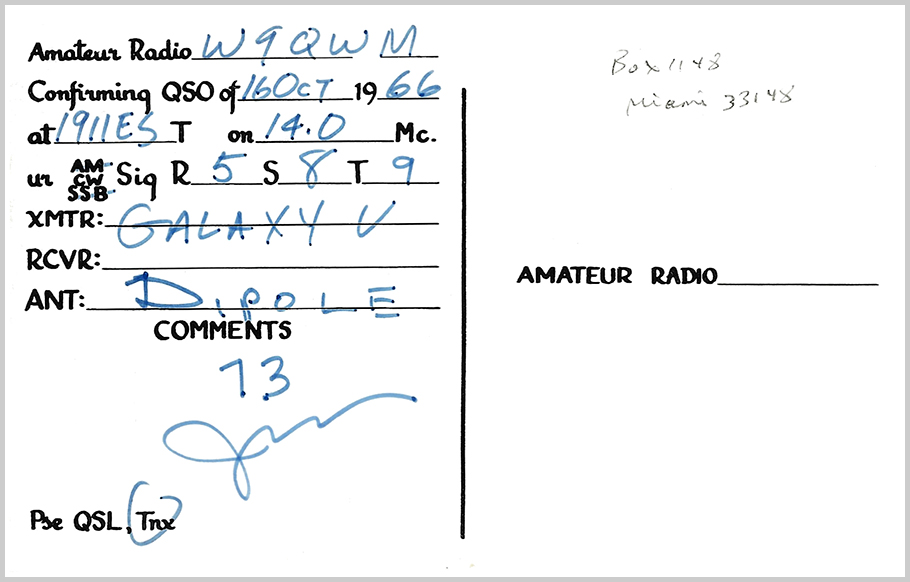

FCC licence?

Tom Kneitel was probably the American journalist who reported most intensively on Radio Swan. Shortly after the start of broadcasting, he asked the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) for licensing information on Radio Swan. In September 1960, he was told that the FCC had no information on the station (C02, page 53). In other words, Radio Swan was broadcasting without a licence. In contrast, the FCC did issue amateur radio licences for Swan Island. Even several Radio Swan/Americas staff and Philco technicians received amateur radio licences as KS4CA, KS4CB, KS4CC and KS4CD (C14, page 17). In the amateur radio call books of the time, the address of Radio Americas is even given as the QSL address for KS4CA (B09, page 606). The amateur equipment available at that time were a 150-watt Allied Knight T-150 and a 500-watt Collins Galaxy F for CW and SSB connections (C10, page 43). Stations of the Federal Aviation Administration (SWA - radio beacon on 407 kHz) and the Meteorological Service (WSG - RTTY connections and voice channel, 2738 kHz, 3329 kHz, 5945 kHz and 9840 kHz) on Swan Island also received call signs from the FCC (C10, page 42 and D01, page 20).

Tom Kneitel was probably the American journalist who reported most intensively on Radio Swan. Shortly after the start of broadcasting, he asked the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) for licensing information on Radio Swan. In September 1960, he was told that the FCC had no information on the station (C02, page 53). In other words, Radio Swan was broadcasting without a licence. In contrast, the FCC did issue amateur radio licences for Swan Island. Even several Radio Swan/Americas staff and Philco technicians received amateur radio licences as KS4CA, KS4CB, KS4CC and KS4CD (C14, page 17). In the amateur radio call books of the time, the address of Radio Americas is even given as the QSL address for KS4CA (B09, page 606). The amateur equipment available at that time were a 150-watt Allied Knight T-150 and a 500-watt Collins Galaxy F for CW and SSB connections (C10, page 43). Stations of the Federal Aviation Administration (SWA - radio beacon on 407 kHz) and the Meteorological Service (WSG - RTTY connections and voice channel, 2738 kHz, 3329 kHz, 5945 kHz and 9840 kHz) on Swan Island also received call signs from the FCC (C10, page 42 and D01, page 20).

KS4CC QSL card (James I Takaki) from October 1966. (Ken Lawrence Collection)

James (KS4CC) was a technician at Radio Americas. (Ken Lawrence Collection)

Time and again journalists asked the FCC about the licensing of Radio Swan/Radio Americas, but were only told that the FCC was aware of the station's existence. As a result of the many enquiries and press reports, access to Swan Island was severely restricted (C17, page 16) and no more KS4 call signs were issued. The FCC even prohibited an amateur radio expedition to Swan Island at short notice (C07, page 100). This was done to maintain at least some degree of secrecy.

In 1965, when asked about the licensing of Radio Americas, FCC employee George O. Gillingham answered: “Government stations don’t have to be licensed – no, forget I said that!” (C09, page 112 and C13, page 68). By this time, however, it was clear to most listeners that Radio Swan/Americas had to be a CIA operation. The CIA's carefully constructed cover as a commercial radio station had developed holes since the Bay of Pigs landing at the latest. Already in the May 1, 1961 issue of Newsweek, Radio Swan was clearly identified as a CIA operation (C04, page 35).

Commercial station?

Doubts about the commercial nature of Radio Swan also arose from the conspicuously low cost of advertising spots. The station charged $24 for a one-minute spot, while New York stations of comparable strength were charging $30 to $60. The difference was even more pronounced when renting a full hour of broadcasting. Radio Swan charged $175, while other stations charged up to $550 (C04, page 6). It is therefore not surprising that the market-experienced PAN American Broadcasting was able to acquire powerful advertising customers for Radio Swan shortly after the start of broadcasting. However, one of the most important advertisers of the time, Campbells', decided against Radio Swan when they learned that large parts of the programme consisted of propaganda (C04, page 6). At the time it was clear to anyone who could do the maths that Radio Swan could barely cover its running costs from advertising revenue. The follow-up station, Radio Americas, also charged similarly low prices for the rental of airtime.

Doubts about the commercial nature of Radio Swan also arose from the conspicuously low cost of advertising spots. The station charged $24 for a one-minute spot, while New York stations of comparable strength were charging $30 to $60. The difference was even more pronounced when renting a full hour of broadcasting. Radio Swan charged $175, while other stations charged up to $550 (C04, page 6). It is therefore not surprising that the market-experienced PAN American Broadcasting was able to acquire powerful advertising customers for Radio Swan shortly after the start of broadcasting. However, one of the most important advertisers of the time, Campbells', decided against Radio Swan when they learned that large parts of the programme consisted of propaganda (C04, page 6). At the time it was clear to anyone who could do the maths that Radio Swan could barely cover its running costs from advertising revenue. The follow-up station, Radio Americas, also charged similarly low prices for the rental of airtime.

After actively participating in the Bay of Pigs landings it was becoming difficult to maintain the cover as a commercial radio station. Hence Radio Swan's office was relocated to Miami (rooms 910, 911 and 912 in the Langford Building, 121 SE First Street) in September 1961. From here Horton Heath (who had hitherto acted as commercial manager) was to run Radio Swan. After about two months, the Gibraltar Steamship Co. and Radio Swan quietly disappeared into the CIA nirvana. The new owner was now the Vanguard Service Corporation which occupied the same rooms as Radio Swan in the Langford Building. Even Radio Swan's telephone number was taken over. The CIA hadn't really put much effort into disguising their new front company, even though the station's name was changed to Radio Americas. The name change probably took place sometime between November 7 and 15, 1961 (C27, page 26).

In mid-1964, the company behind Radio Americas changed again. The new owner now was Radio Americas Inc. at 101 Madeira Avenue in Coral Cables, a suburb of Miami (C27, page 28). This, too, was a front company for the CIA. In the shortwave broadcasts, Radio Americas gave an address in Caracas, Venezuela. In this way, the letters could be separated according to short and medium wave listeners and reception areas (C09, page 51).

Swan Island form the emergent crest of the Swan Island Ridge and are perched 5300 m above the adjacent floor of the Cayman trough. The two Swan Islands reach a maximum topographic elevation of 10 m.

The actual location?

A very big topic that was discussed controversially for many years was the "alleged" transmitter location on Swan Island (C27, page 1). In late February 1960, three radio amateurs were active from Swan Island for eight days during the ARRL CW DX contest under the callsign KS4AZ. They had not observed any activities to set up a radio station (C01, page 52).It was hard to imagine at the time that it would be possible to set up a 50-kW transmitter on this remote island in less than three months.

A very big topic that was discussed controversially for many years was the "alleged" transmitter location on Swan Island (C27, page 1). In late February 1960, three radio amateurs were active from Swan Island for eight days during the ARRL CW DX contest under the callsign KS4AZ. They had not observed any activities to set up a radio station (C01, page 52).It was hard to imagine at the time that it would be possible to set up a 50-kW transmitter on this remote island in less than three months.

Ethel M. Crowell's eyewitness account, published in the Fallmouth Enterprise on July 6, 1962 (C34), could have curtailed years of speculation and sometimes heated debate about the transmitter's location. However, this newspaper report did not become known in shortwave listening circles until several years later. During her stay of several days on Swan Island with the purpose of historical research on guano mining, Ms Crowell was looked after by Roger Butts, Vice President of the Vanguard Service Corporation. He was managing Radio Americas' operations on the island at the time. Ms. Crowell was housed in one of the Quonset huts (a lightweight, prefabricated structure made of corrugated iron with a semi-circular cross-section) that the Seabees had built. Little is learned from Ms. Crowell about the operation of Radio Americas, though her account does contain information about the comfortable living conditions of the staff (rarely mentioned in other sources). For example, her Quonset hut had five rooms and a bathroom with hot and cold running water. A seawater desalination plant provided fresh drinking water and the rich food gave her no reason to complain.

In February 1968, Tom Kneitel was the first and only journalist to be granted permission to visit Radio Americas. Probably the CIA already had the end of Radio Americas (on May 15, 1968) in mind and had no more reservations about letting a journalist visit the island (C15, page 22). Over the past few years, Tom Kneitel had published many investigative articles on Radio Swan/Americas and its ties to the CIA. Now he had also succeeded in finally solving the mystery of the location (C09, page 45 - C14, page 16 and C15, page 18). According to his report, the residential buildings and studio and office space were in the south-west part of the island, while the antennas and transmitters were in the south-east. He reported that the ageing transmitters were housed on trailers, which solved the mystery of the station's rapid construction as well.

Even more Swan?

Further confusion as to Radio Swan's actual location was fueled by rumors that the station was broadcasting from a ship. In fact, there were broadcasts from the "Matusa Time". Again, the CIA had a hand in this (A02, page 5), but these were broadcasts from "Radio Cuba Independiente" (C21, page 11 and C29). Similar to Radio Swan, these broadcasts were created by Cuban exile groups (A11, page 131 und A23). Allegedly, in the run-up to the Bay of Pigs landing, the CIA had also hired three ships to broadcast CIA-controlled programmes on medium and short wave, similar to Radio Swan (A11, page 23 and page 48). However, these three ships never left Miami. Moreover, they did not have the necessary technology and personnel on board to be able to transmit at all (A11, page 106).

Further confusion as to Radio Swan's actual location was fueled by rumors that the station was broadcasting from a ship. In fact, there were broadcasts from the "Matusa Time". Again, the CIA had a hand in this (A02, page 5), but these were broadcasts from "Radio Cuba Independiente" (C21, page 11 and C29). Similar to Radio Swan, these broadcasts were created by Cuban exile groups (A11, page 131 und A23). Allegedly, in the run-up to the Bay of Pigs landing, the CIA had also hired three ships to broadcast CIA-controlled programmes on medium and short wave, similar to Radio Swan (A11, page 23 and page 48). However, these three ships never left Miami. Moreover, they did not have the necessary technology and personnel on board to be able to transmit at all (A11, page 106).

From July 1975 to mid-1977, the name Radio Swan was used again by a station in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. It broadcast on 6185 kHz, then 6000 kHz and later 6015 kHz (D04, page 2). The programmes contained anti-Castro propaganda, a connection with the original Radio Swan cannot be proven and is unlikely.

Replacement for Radio Swan?

Mediumwave transmitter with 1000 kW?

In May 1962, Edward R. Murrow, Director of the United States Information Agency (USIA, also known as United States Information Service - USIS) prepared a memorandum for Brigadier General Edward Geary Lansdale (head of Operation Mongoose) on the possibility of setting up a new medium-wave station to broadcast programmes to Cuba (A24, page 43 to 52). This new station was to replace Radio Americas, since the CIA was also aware that Radio Americas - despite the name change - had lost its credibility after its tactical involvement in the Bay of Pigs landing (A24, page 42 and page 48) and was not really effective with Cuban listeners (A17, page 3).

In May 1962, Edward R. Murrow, Director of the United States Information Agency (USIA, also known as United States Information Service - USIS) prepared a memorandum for Brigadier General Edward Geary Lansdale (head of Operation Mongoose) on the possibility of setting up a new medium-wave station to broadcast programmes to Cuba (A24, page 43 to 52). This new station was to replace Radio Americas, since the CIA was also aware that Radio Americas - despite the name change - had lost its credibility after its tactical involvement in the Bay of Pigs landing (A24, page 42 and page 48) and was not really effective with Cuban listeners (A17, page 3).

Edward Murrow stated in his report that the high level of credibility of the Voice of America (the VoA was part of the USIA) must be maintained at all costs. Harder propaganda broadcasts should only be aired by a covert operation (A24, page 52). In August 1962, nine possible locations in and around the Caribbean were surveyed (A24, page 12 to 22) and discussed in various papers (collected in A24). From almost all locations, a 1000 kW transmitter could have delivered a sufficient signal into Cuba. Apart from the extremely high financial and logistical effort, one would also have had to contend with political imponderables at foreign locations and the problem of frequency coordination for such a powerful transmitter. Furthermore, Fidel Castro could have jammed the reception of this new channel in almost all of Cuba (A24, page 18 and 19). A USIA report from September 1962 (A18) outlines the situation at the time with regard to existing transmissions directed to Cuba by the VoA, Radio Americas and four US stations. In addition, the barely manageable legal/political problems of a new, strong broadcaster were discussed.

Radio Free Cuba

As an alternative, William King Harvey, one of the most important agents of the time, suggested setting up a radio station "Radio Free Cuba" in southern Florida and close down the station on Swan Island (A15, page 4). This is probably the first mention of Radio Free Cuba, the forerunner of "Radio Marti", launched in May 1985.

As an alternative, William King Harvey, one of the most important agents of the time, suggested setting up a radio station "Radio Free Cuba" in southern Florida and close down the station on Swan Island (A15, page 4). This is probably the first mention of Radio Free Cuba, the forerunner of "Radio Marti", launched in May 1985.

In a memorandum dated August 31, 1962 (A16, page 8), Brig. Gen. Lansdale advocated continuing Radio Americas and other CIA-sponsored radio broadcasts for the time being: "to irritate the Castro regime." In a document dated November 27, 1962, this sentence was repeated almost verbatim (A20, page 14).

In order to prevent a "radio war", under which the reception of many commercial US stations would also have suffered, the CIA did not pursue the plan for a new, strong medium-wave transmitter. Instead, on October 20, 1962 (against the background of the Cuban Missile Crisis), President Kennedy requested the USIA to significantly increase its programmes towards Cuba (B06). The stations belonging to the USIA network, WGBS (Miami), WMIE (Miami), WSB (Atlanta), WWL (New Orleans) and WKWF (Key West), transmitted programmes on airtime (allegedly) rented by exiled Cuban groups. Radio Americas was also able to extend its raison d'être. VOA also maximized its Spanish programmes (A19, page 3 and B02, page 18/26) by launching two new stations in Florida in 1962 (D08).

Secret VOA station

Among these new transmitters was a secret station used by the VOA for broadcasts to Cuba, but which could have taken on other tasks such as jamming in the event of an armed incident (which was not unlikely during the Cuban Missile Crisis). Details of this transmitter remained unknown for a long time (C11, page 66). It was not until 1969 that a VOA employee confirmed that there had been a transmitter on Dry Tortugas. Further information came to light in 1998 by a former employee of this station (C19, page 13) and in 2004 by historians in Florida (B10, page 38). Accordingly, a 20-year-old mothballed 50 kW transmitter (Westinghouse 50G) formerly used at WBAL was made operational again and brought to Fort Jefferson on Garden Island by the Navy on five trailers in October 1962 (at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis) (D08). Garden Island is part of the Dry Tortugas, seven small uninhabited coral islands at the end of the Florida Keys, about 113 km west of Key West, Florida. The Navy-run station aired takeovers from VOA, but occasionally from Radio Americas as well(C11, page 66). The station, broadcasting on 1040kHz, operated for only three months (October to December 1962). In January 1963 it was dismantled and rebuilt at a new location (Sugarloaf Key - near the Key West Naval Air Station). From there the station continued to transmit on 1040 kHz. The no longer secret Sugarloaf Key location was officially confirmed by VoA on QSL cards. After a hurricane destroyed the antennas in 1966, the Sugarloaf Key site was abandoned and the transmitter put back into storage. At the former Marathon Key site of the VOA, it is said to have been used again later for transmissions by Radio Marti.

Among these new transmitters was a secret station used by the VOA for broadcasts to Cuba, but which could have taken on other tasks such as jamming in the event of an armed incident (which was not unlikely during the Cuban Missile Crisis). Details of this transmitter remained unknown for a long time (C11, page 66). It was not until 1969 that a VOA employee confirmed that there had been a transmitter on Dry Tortugas. Further information came to light in 1998 by a former employee of this station (C19, page 13) and in 2004 by historians in Florida (B10, page 38). Accordingly, a 20-year-old mothballed 50 kW transmitter (Westinghouse 50G) formerly used at WBAL was made operational again and brought to Fort Jefferson on Garden Island by the Navy on five trailers in October 1962 (at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis) (D08). Garden Island is part of the Dry Tortugas, seven small uninhabited coral islands at the end of the Florida Keys, about 113 km west of Key West, Florida. The Navy-run station aired takeovers from VOA, but occasionally from Radio Americas as well(C11, page 66). The station, broadcasting on 1040kHz, operated for only three months (October to December 1962). In January 1963 it was dismantled and rebuilt at a new location (Sugarloaf Key - near the Key West Naval Air Station). From there the station continued to transmit on 1040 kHz. The no longer secret Sugarloaf Key location was officially confirmed by VoA on QSL cards. After a hurricane destroyed the antennas in 1966, the Sugarloaf Key site was abandoned and the transmitter put back into storage. At the former Marathon Key site of the VOA, it is said to have been used again later for transmissions by Radio Marti.

The sources

Thanks to everyone who helped me with my research!

Radio Swan was not a stand-alone CIA project, but rather an integral part of the attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro. The highlight was the failed landing in the Bay of Pigs. The sometimes hair-raising mistakes and misjudgments of the CIA were pointed out relatively quickly in internal investigation reports. On many hundreds of pages, Radio Swan often only appeared in individual sentences that had to be painstakingly picked out and put into context. For a long time, the CIA refused to make these and other documents public (A01, A04 and A05). Only gradually, sometimes after long legal proceedings, did the public gain insight. At the instigation of President Biden, another large batch of documents was released in December 2022.

Radio Swan was not a stand-alone CIA project, but rather an integral part of the attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro. The highlight was the failed landing in the Bay of Pigs. The sometimes hair-raising mistakes and misjudgments of the CIA were pointed out relatively quickly in internal investigation reports. On many hundreds of pages, Radio Swan often only appeared in individual sentences that had to be painstakingly picked out and put into context. For a long time, the CIA refused to make these and other documents public (A01, A04 and A05). Only gradually, sometimes after long legal proceedings, did the public gain insight. At the instigation of President Biden, another large batch of documents was released in December 2022.

Another important source of information from the point of view of the listeners at the time were the reports by Tom Kneitel († Aug. 22, 2008 - C22, page 4) and other authors in the radio magazines of the 1960s. Thanks to worldradiohistory.com, almost all of these magazines were freely accessible.

I would also like to thank Chet Reuter, who first drew my attention to this station through his presentation at Radiotag 2022, as well as Richard Cummings (RFE/RL's head of security from 1980 to 1995) and Ken Brown (RFE/RL's network engineer) whose research on CIA clandestine stations and the transmitters used for Radio Swan I was allowed to take over.